Single model predicts trends in employment, microbiomes, forests

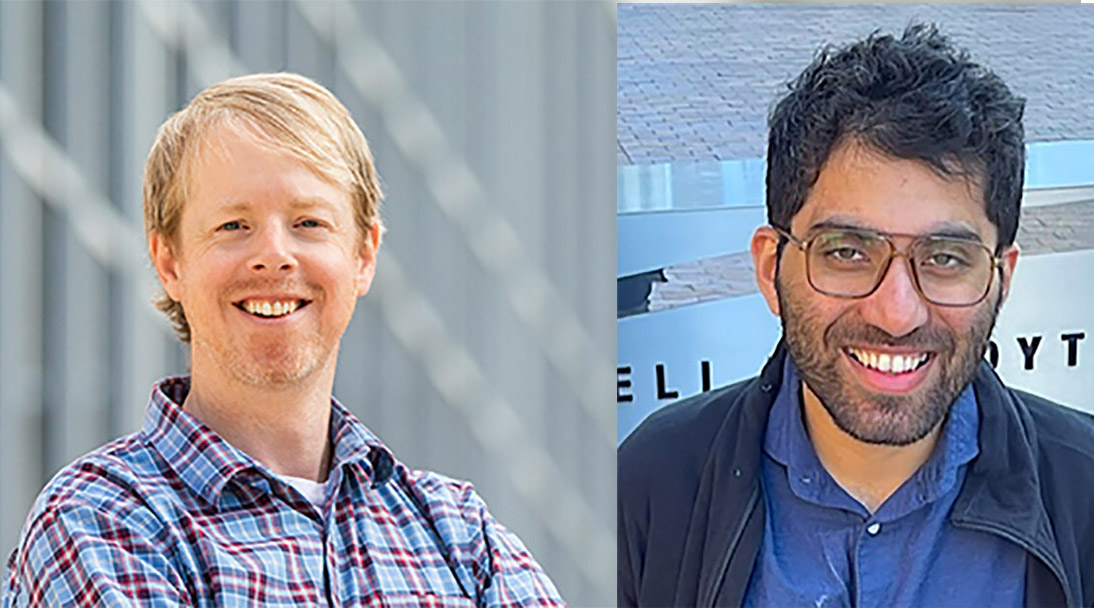

U. of I. plant biology professor James O’Dwyer (left) reports the development of a single model that can predict patterns of population fluctuations in social and biological realms. O’Dwyer and study co-author Ashish George (right) detail their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. / Michelle Hassel and Venus Trent

Researchers report that a single, simplified model can predict population fluctuations in three unrelated realms: urban employment, human gut microbiomes and tropical forests. The model will help economists, ecologists, public health authorities and others predict and respond to variability in multiple domains, the researchers say.

The new findings are detailed in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The model, which goes by the acronym SLRM, does not predict exact outcomes, but generates a narrow distribution of the most likely trajectories, said James O’Dwyer (CAIM), a professor of plant biology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who developed the model with postdoctoral researcher Ashish George in the IGB. George is now a computational scientist at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“The model incorporates random events, so it predicts a range of outcomes. But the data fall right in the middle of that range of outcomes,” O’Dwyer said.

The model divides each population into discrete sectors – for example job types such as healthcare, agriculture or retail trade – and assigns a “generation time” to each.

“Generation time is the lifetime of a tree or microbe, or the time a person spends in a given employment sector,” George said. “It is measured in hours for microbes, years for job types, and decades for forests.” Analyzing the systems in terms of generation time for each sector revealed similarities in how all three systems behave.

The scientists relied on decades of research tracking changes in each of the different domains over time. For the employment analysis, they focused on the number of people employed in different economic sectors over time. This data came from the North American Industry Classification System and included monthly updates for 383 U.S. cities over a period of 17 years.

The forest data came from a study that tracked tree and shrub species every five years for two decades in a 123-acre plot on Barro Colorado Island in Panama. And the microbiome data was from a study measuring the relative abundance of hundreds of microbial species in the human gut every day for more than a year.

“For each ‘species’ in each system, we analyzed the trajectory of relative abundances across numerous time points to estimate three quantities: an equilibrium abundance, how long it takes for a trajectory to return to equilibrium after a perturbation, and a strength of stochasticity,” George said. “The stochasticity incorporated into the model accounts for the random events that generate fluctuations away from or back toward equilibrium.”

“We found a good description of the majority of the data with this model,” O’Dwyer said. “Simple as it is, we compared it with some other alternative models, and it performed better. Our model describes the patterns of fluctuations very well.”

“The simplicity of the model allows it to be applicable across both biological and social realms,” O’Dwyer said. “It can predict changes in abundance, but it cannot describe the exact cause of those fluctuations.”

Understanding the detailed mechanisms that generate the fluctuations would need in-depth, system-specific analyses, he said.

“This is the first effort to unify predictions for fluctuations across these domains using the same model,” George said. “This advance will not only aid in developing new prediction methods in each system, but also motivate the cross-pollination of concepts and techniques across these seemingly disparate fields.”