BIOMARKER

Volume 19

Director's Message

Since the release of ChatGPT by OpenAI in late 2022, generative artificial intelligence technology has quickly permeated our society. Few areas of human endeavor have not been touched by current AI developments; from tasks as everyday as writing an email or looking up a recipe to challenges like developing a new cancer therapy or predicting the irrigation dynamics of crops, our society is exploring what AI has to offer.

While AI has swept our collective consciousness, our collective conscience is moving with more deliberation. Any new technology, especially those with manifold applications, necessitates a societal conversation to answer questions regarding its use: How? When? By whom? For what? AI’s broad-reaching nature also places a responsibility on practitioners in each field it touches to shape its ethical and effective use.

At the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, we are helping to lead in envisioning the future of AI-assisted biology. In the years preceding ChatGPT’s release, our members have founded the Illinois Biological Foundry for Advanced Biomanufacturing, the Center for Genomic Diagnostics, and the Molecule Maker Lab Institute, all powered in part by AI. A research theme established in September 2022, the Center for Artificial Intelligence and Modeling, aims specifically to guide our research community in AI applications. We are actively exploring what AI can do for genomic biology.

Thanks to this work, our plans for AI are informed by our growing understanding of its present and predicted strengths, as well as its drawbacks. In this online edition of Biomarker, we invite you to explore how these conversations are unfolding within the IGB community. We revisit the years of slow progress, punctuated by technological breakthroughs, that have transformed our ability to synthesize the monumental volumes of data produced by next-generation DNA sequencing and other large-scale experimental techniques. We reflect on the strengths and potential failings of AI as a tool to make predictions about the ecosystems we live in, and those that live within us. We look back on what these types of computational tools have enabled us to discover so far and share what new insights we hope they may yield in the near future.

We hope this inside view captures the nuanced reality of AI as a revolutionary technology and inspires you to think about it in new ways. As we look ahead, we welcome your voice in the ongoing discussion of where we go from here.

Gene E. Robinson

IGB Director

How we got here

Computer scientists, mathematicians, statisticians, and engineers are a subset of the many people who have built the foundation for what we now call AI. As research continues to grow more interdisciplinary, AI researchers have teamed up with life scientists to innovate new AI tools to meet the demands of modern biological research. Since the institute’s founding in 2007, IGB researchers have helped drive the application of AI to life sciences research, supported by Illinois campus institutions like the Grainger College of Engineering and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications.

The IGB was established just a few years after the completion of an international interdisciplinary effort, the Human Genome Project. This accomplishment, which yielded three billion base pairs of DNA sequence, was a starting point for the generation of vast amounts of genomic data as researchers seek to better understand how the genome shapes life. But in order to draw meaning from these large data sets, researchers need ways to make sense of billions letters spelling out a nonintuitive molecular language.

Bioinformatics, a field which lies at the intersection of biology and computation, fills this gap, providing practical tools to find connections and uncover patterns hidden in genomic data. This is particularly important as genomic data sets have continued to grow, necessitating computational developments for data acquisition, storage, analysis, and integration.

While the traditional Sanger sequencing methods employed during the Human Genome Project could sequence one DNA strand at a time, next-generation sequencing handles millions in parallel. Adopted around the turn of the century, these NGS methods have become more cost effective and globally accessible over the past 20 years, allowing scientists to ask new questions and collect new types of data.

As genomics has exponentially expanded past traditional DNA analysis, AI can be a valuable bioinformatic tool to meet this demand, helping to analyze massive amounts of data and speed up scientific studies. Within the scientific community, the release of transformative programs like AlphaFold catalyzed a new awareness and excitement about AI’s potential. This rapid rise obscures the preceding 75 years of research and development that made these technologies possible.

Coined in 1956, the term “artificial intelligence” described work focused on the science and engineering of computer systems that mimic human intelligence. Throughout the years, AI has gone through cycles of heightened public interest followed by disappointment, such as in the ‘AI winter’ of the 1980s when the industry crashed. But even in times of decreased public hype, researchers and developers continued to innovate these technologies.

“When I was working on an area called compressive sensing and low-rank matrix completion 16 or 17 years ago, it fell under the umbrella of signal processing and statistics,” said Olgica Milenkovic (CAIM co-leader/BSD/CGD/GNDP). “All these disciplines that are now collectively referred to as machine learning existed a long time ago, except that they were scattered around different fields.”

In 2014, Huimin Zhaoprofessor of chemical and biomolecular engineering (BSD leader/CAMBERS/CGD/MMG) led the establishment of the Illinois Biological Foundry for Advanced Biomanufacturing, positioning the IGB at the forefront of integrating AI and automation to optimize laboratory workflows. The iBioFab runs automated experiments, improving the speed and accuracy of complex biosynthetic and genomics lab processes. With a robotic arm that moves samples between 40 different instruments and integration with AI tools, the system can adapt to the unpredictable nature of biological experiments, handle large amounts of data, and optimize users’ workflows.

These capabilities have only expanded over the past 10 years with the opening of iBioFab II and, most recently, the iBiofoundry, promoting advances in synthetic biology and biotechnology to address major biological challenges. Building upon the success of the iBioFAB, the Molecule Maker Lab Institute was founded in 2020, with the goal of developing new AI methods to accelerate molecular innovation and democratize chemical synthesis.

Over the last three quarters of a century, the fields of genomics and AI have been growing and evolving in parallel toward this moment of intersection. For the IGB community, iBioFab and MMLI were part of the first wave. Let’s go back in time and see how AI is converging with genomics.

MODELING INTELLIGENCE, MODELING LIFE

The earliest roots of machine learning actually predate computers, emerging from the quest to understand our own intelligence. Beginning in the late 1800s, scientists speculated that thoughts and memories are represented in the brain by connections between neurons and the electrical impulses that flow among them. Over subsequent decades, they refined these ideas, working to create conceptual, mathematical, and eventually computational models of how an interconnected network of neurons, through signaling, can learn, store information, and respond to stimuli.

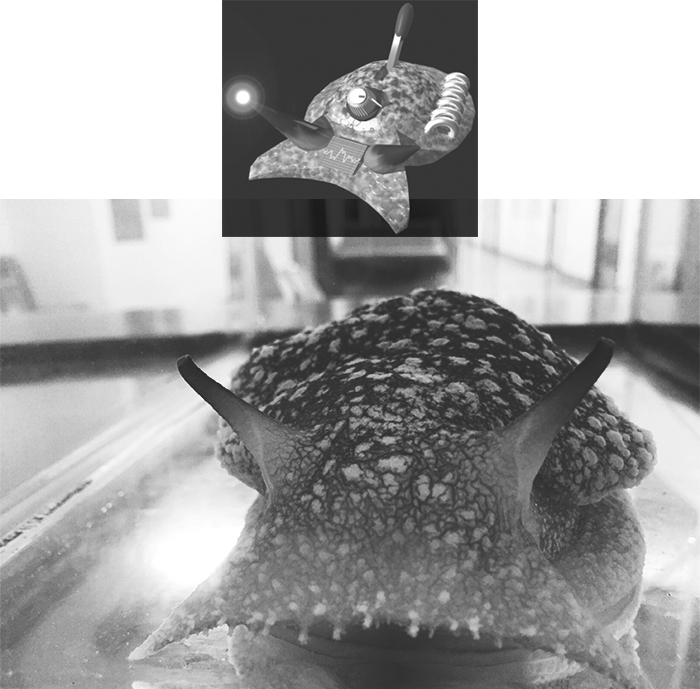

As that work has advanced, neural network modelers aiming to reproduce the capabilities of very simple animal brains have achieved surprisingly true-to-life results. One example comes from the lab of Rhanor Gilletteprofessor of molecular and integrative biology (GNDP). Over the last decade, he and his colleagues have continuously improved a model of the simple but flexible brain of the predatory sea-slug Pleurobranchaea. Like its biological inspiration, the virtual slug they created from experimental data can identify when it is “hungry,” pursue simulated nutritious “prey” while avoiding toxic food sources, and stop when it is “full.”

In the 1950s, the promise of biological neural network models caught the attention of early computer scientists. They launched an effort to teach computers, not just to improve our understanding of the brain, but to outsource some of its functions. This parallel trajectory of research was the path to modern AI, leading through the field of machine learning. The goal of machine learning is to create an algorithm that is able to take in a data set, often a very large one, and extract patterns in those data that can be reliably used to analyze future experiments. The applications of this approach were as broad as the types of data that an algorithm could be programmed to handle, from identifying fossilized pollen grains by shape to summarizing gene functions to discerning movement patterns in people with respiratory issues. At their best, machine learning models home in on patterns that a human researcher might not be able to notice.

Machine learning is not supplanting traditional mechanistic modeling, however, in which scientists use math as a language to describe the functioning of a living system and relationships between factors that influence it. In one sense, machine learning bypasses this work, synthesizing data directly into a model built on a multitude of factors unknown to the researcher. This approach has advantages and disadvantages.

“AI may be incredibly important from a practical standpoint, but it may not be that useful for understanding how systems work. Whereas what really helps you to understand are mechanistic models. And the simpler this model is, the better off you are in terms of understanding . . . because the worst outcome [would be that] we'll just be happy with a situation where AI gives us answers without explaining why.”

—Sergei Maslov (CAIM co-leader)

professor of bioengineering

This perspective hints at the relative weaknesses and strengths of computational approaches in modeling. While it cannot replace human comprehension of biological ideas or decide on its own what is meaningful to humans, it can reckon with the type of large and complex data sets that modern research methods sometimes produce. Hee-Sun Hanprofessor of chemistry (IGOH/GNDP) and Dave Zhaoprofessor of statistics (GNDP) leveraged this capability when they developed InSTAnT, a computational toolkit that is able to synthesize information about when and where many different types of proteins are being produced within a cell. Converting very large data sets into a single integrated map enables researchers to construct stronger hypotheses about how proteins work together to achieve cellular functions.

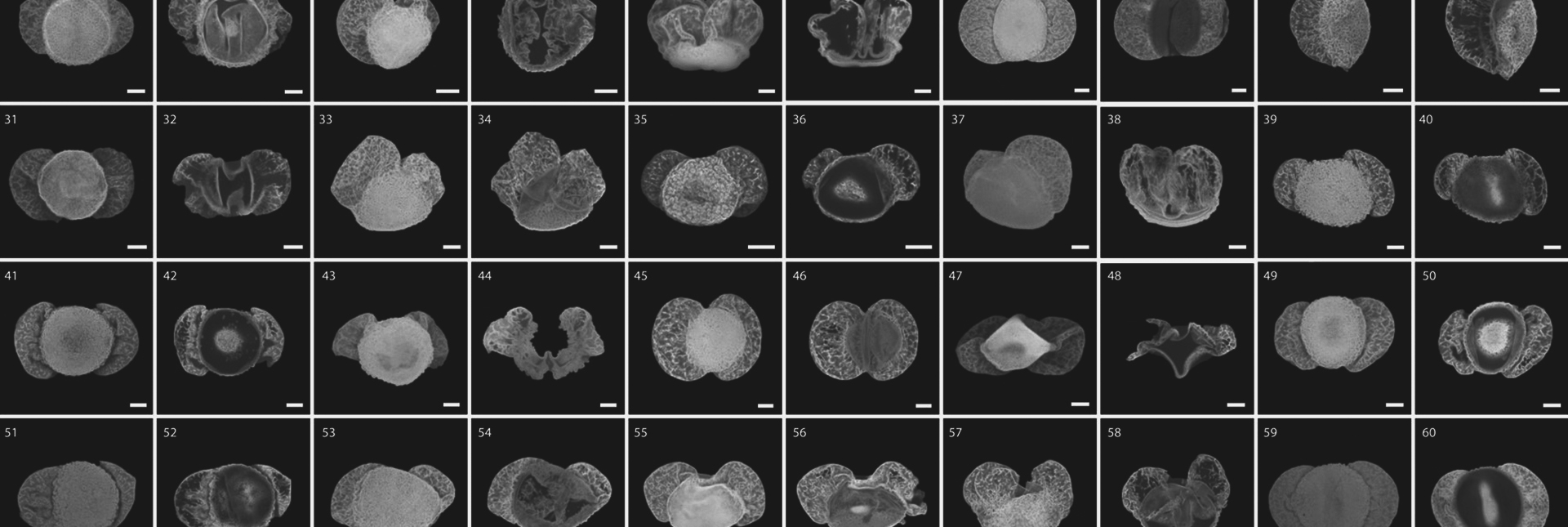

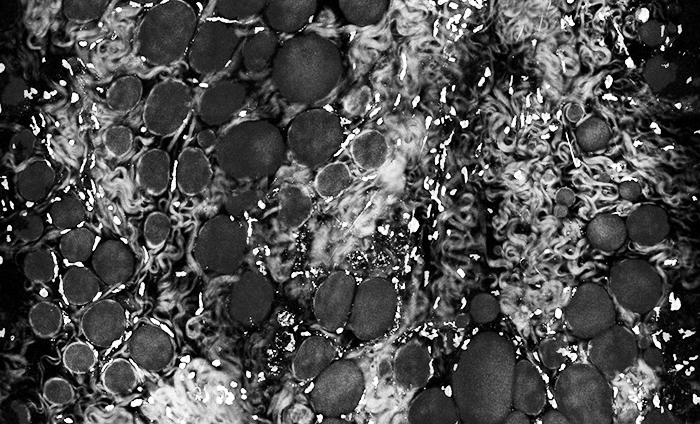

More recent efforts to understand the brain from the bottom-up rather than the top-down showcase this use of machine learning as well. Jonathan Sweedlerprofessor of chemistry (BSD/CAMBERS/MMG) and Fan Lamprofessor of bioengineering (GNDP) developed an imaging method to visualize some of the molecular building blocks and chemical signals of the brain. By integrating this imaging framework with deep learning, they created detailed, 3D maps of how these chemicals are distributed. The deep learning data reconstruction method they employed made it possible to compile massive amounts of data into a comprehensible visual display of how neurons function in health and disease.

Whether a model is constructed by a human or an algorithm, it must be subjected to a scientifically rigorous reality check. Scientists test their models through real-world experimentation, setting up conditions represented in the model and comparing the results to those that the model predicted. For some applications of AI and its forerunners, generating predictions isn’t just a way to validate a model, but its primary purpose.

How We Got Here

READING GENOMES AND PHENOTYPES TO SEE THE FUTURE

Prediction is a fundamental activity of science. In biology, it is an endeavor that pushes us to organize our understanding of relationships between aspects of life. In 1911, botanist Wilhelm Johannsen invented the terms “genotype” and “phenotype” to frame what would turn out to be one of the central questions of genomics over a century later: what is the relationship between variation in heritable material and variation in physical traits of living things?

Even as the meaning of these terms has evolved and advances in our understanding of DNA, genes, and the genome have clarified many mysteries of nature, we are still striving for the ability to relate genotype to phenotype; to trace a connection to, or even predict, an organism’s form from the information contained in its genome. What makes this challenging is the staggering scale of factors involved. The genomes of most organisms contain thousands of genes whose functions are impacted by each other and by the environment.

Big data-producing biological research methods have finally moved us closer to elucidating this web of interconnections. To do so, we need data from both sides of the genotype-phenotype equation. On the genotype side, we have a suite of DNA technologies led by next-generation sequencing. On the other, methods of measuring phenotype must be as varied as are traits of interest: characteristics as fleeting as the behavior of a fish toward its offspring or as concrete as a microbe’s capacity to produce a particular substance. In crop development research, we find both. Across many acres of crop plants, scientists have found ways to measure traits ranging from the microscopic and momentary changes in a leaf’s metabolism to the vast and vital quantity of a crop’s eventual yield of food or fuel.

Testing new crops being developed to withstand severe weather requires researchers and crop breeders to track key traits like plant emergence and height. To perform this laborious process in row after row of plants, researchers set out to develop a compact, deep learning-enabled robot, now called TerraSentia. As it autonomously navigates rows of crops and captures data for each plant using its cameras and sensors, it saves the human researchers time and energy to focus on other tasks.

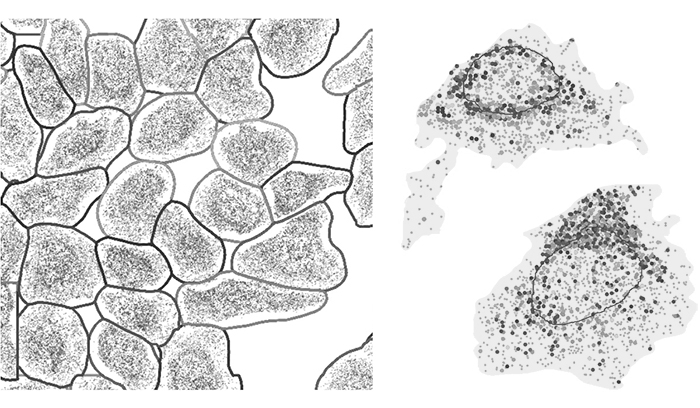

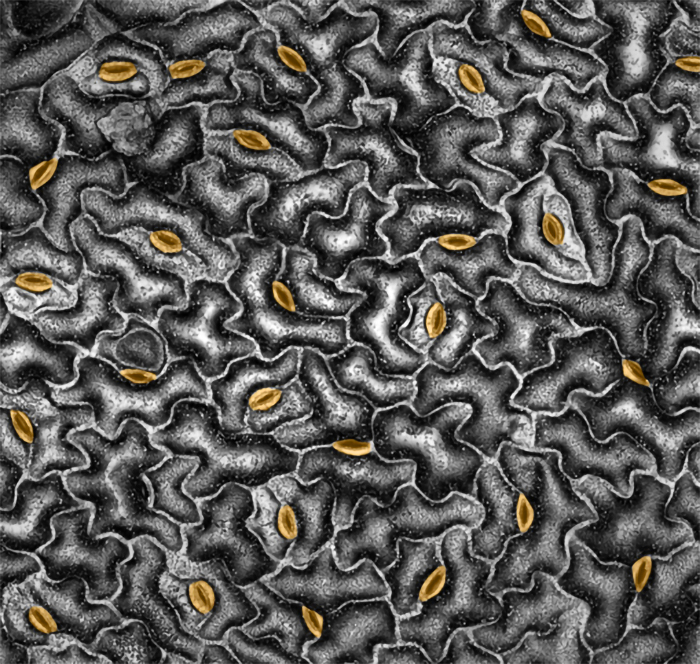

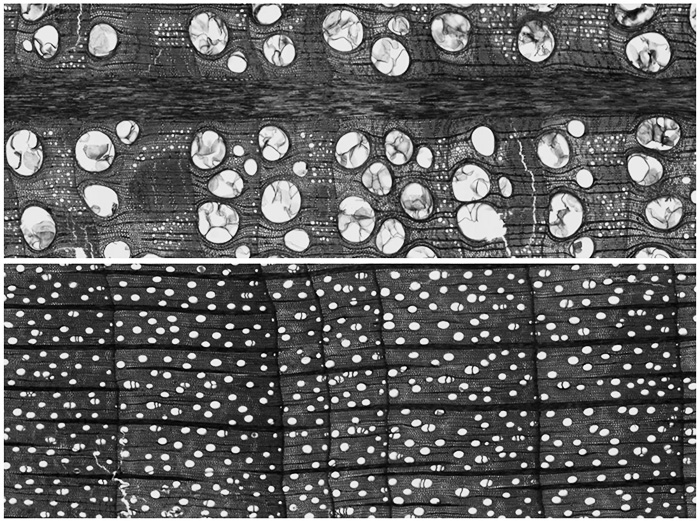

On a much finer biological level but producing a volume of data just as large, research led by Andrew Leakeyprofessor of plant biology (CAMBERS leader/PFS) has employed AI tools to discover traits that can help crop plants conserve water in drought conditions without sacrificing yield. The team adapted a machine learning method to identify, count, and measure thousands of cells and pores, called stomata, on leaves’ surfaces.

“I had a very good graduate student who said, 'I would like to go try to train one of these models in parallel.’ . . . It was a very definable moment where suddenly we had the capability to automatically process thousands, tens of thousands of images, where before that process took students counting cells manually. That to me was the state change where suddenly AI could do things for me.”

—Andrew Leakey (CAMBERS leader/PFS)

professor of plant biology

With the data in hand, Leakey's lab group used statistical methods to link the crops’ physical traits to regions of its genome to better understand how genes control the patterning of stomata. Meanwhile, another group led by Madhu Khannaprofessor of agricultural and consumer economics (CAMBERS), Jeremy Guestprofessor of civil and environmental engineering (BSD/CAMBERS), and DoKyoung Lee have worked the crop development problem from the other end. With the help of more traditional modeling, they have integrated regional data on biofuel crop yield, soil carbon, farming costs and emissions, and climate to predict what crops will be most sustainable to grow in specific areas of the US. While these studies have not yet involved AI in their analyses, predictive AI offers the possibility of broadening this type of finding.

Recognition is growing of the potential applications of predictive AI methods. As we consider how to make sure the flora we are surrounded by can continue to feed us, we are also turning to machine learning to help us predict how to feed the flora that we contain. Hannah Holscherprofessor of food science and human nutrition (CAIM/MME), Sergei Maslovprofessor of bioengineering (CAIM co-leader) and their colleagues constructed a deep learning model able to predict how an individual’s gut microbiota, the population of bacteria, archaea, and yeast cells that live in our digestive tract, responds to changes in diet. Studies like this one offer a possible future in which approaches to wellness could be personalized to the unique needs of each individual.

THROUGH A LENS CLEARLY

The history of medical science is a history of close observation, seeing and trying to understand the ways in which a malady of the body is causing distress. Humans began trying to care for one another long before we understood anything about how the body actually works on a cellular level or even knew cells existed; modern medical science was built from this humble start through centuries of scientific and medical research. Progress often occurs in incremental steps, carried forward by scientists across the world. But sometimes, a new scientific discovery or technological advancement, like the invention of the microscope in 1600 or the discovery of x-ray in 1895, catalyzes a larger cascade of innovation.

These advances are noteworthy in part because they extend medical observation beyond what a human can do. Machine learning, computer vision, and increasingly, AI held the promise of doing the same. Computers don’t get tired; sensors don’t view a light signal differently because of dry eyes. Automating aspects of disease detection and diagnosis offered a new way to bring objectivity to a consequential and sometimes enigmatic aspect of healthcare.

With a clear understanding of AI’s strengths and limitations, combined with a grounding in human-oversight, tasks can be off-loaded to AI to save time, labor, costs, and resources. For example, a research study led by Mehmet Ahsenprofessor of business administration (CGD) demonstrated how hospitals and clinics could strategically implement AI for breast cancer screening, potentially reducing costs up to 30%. While AI was tasked with initial screens and triaging low-risk mammograms, radiologists could use their time and expertise to assess cases flagged as high-risk or ambiguous.

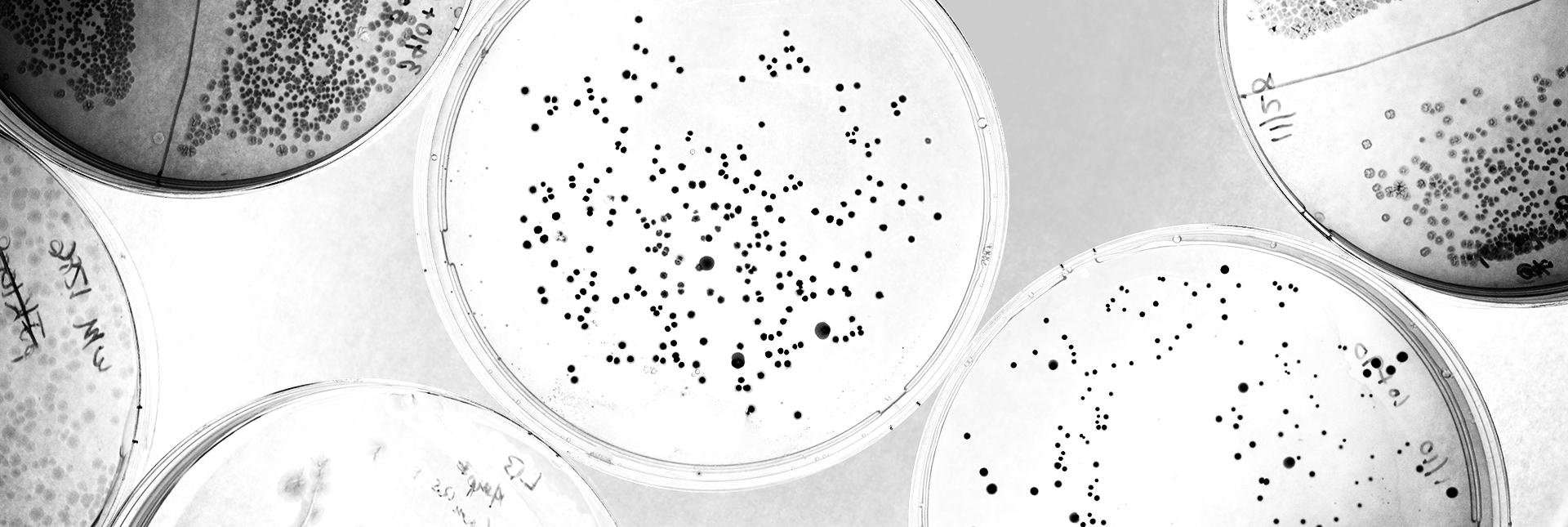

Research in Brian Cunningham’sprofessor of electrical and computer engineering (CGD leader) group also takes advantage of human-computer partnerships to evaluate data, using AI to help improve the detection of biomarkers—molecules that can indicate what is happening in the body, as well as the presence of disease. Their microscopy-based diagnostic technique generates red images with tiny black spots scattered throughout, each representing a single biomarker molecule tagged with a gold nanoparticle for visualization. Integration of a deep-learning algorithm helps to automate the counting of these spots, improving the accuracy and lowering detection limits of their method.

While the automation helps remove the need for expert analysis, the AI’s performance is tied with the quality of its training data. A speck of dust can be difficult to differentiate from a true biomarker spot, even to the trained eye. To ensure accurate counting, graduate student Han Lee spent hours cross referencing black spots against ground truth electron microscope images.

“I think that the limitation is that AI can't, by itself, actually detect the molecules. We still need the physics principles, the nanofabrication, the optics, electromagnetics, and biochemistry parts to all work together to selectively capture the biomarker and provide a signal that is above the background noise. What the AI helps with is the ability to tolerate a greater degree of background noise, so we can use less costly optical components to build a small and inexpensive instrument.”

—Brian Cunningham (CGD leader)

professor of electrical and computer engineering

Another role AI can fill, though, is helping to identify new sources of biomarkers. By innovating and improving diagnostic biosensing, clinicians can detect disease earlier, ideally before symptoms emerge. One area of medicine where this might make the biggest difference is cancer detection and diagnosis. Cancer begins with genetic changes to the patient’s own cells. Where we once described cancers based on where they occurred or what tumors looked like to our eyes, microscopy and genomics have allowed us to look deeper. Even though there are common changes across types of cancers, the same type of cancer varies widely in how it develops and behaves, not only from person to person, but also within different parts of a tumor.

With the help of AI, scientists can probe these differences, often referred to as tumor heterogeneity, and suggest new molecules to assess for use as biomarkers. Georgia Tech professor of biomedical engineering Saurabh Sinha and professor electrical and computer engineering Stephen Boppart developed a new microscope to better understand the tumor environment. With their specialized laser source, the team could directly observe optical properties of native molecules, cells, and tissues without needing any external dyes or contrast agents. Instead, deep-learning algorithms were able to digitally mark and identify different cell types in images.

Other work examining tumor heterogeneity was performed by Mohammed El-Kebirprofessor of computer science (CAIM/IGOH), who has directed AI at large quantities of genomic data. With a combination of AI algorithms and mathematical models, El-Kebir pieced together cancer phylogenies to understand how cancer develops. These methods can also be used to help identify new biomarkers to target by showing how a cancer’s formation and spread may work on a cellular level.

With their ability to integrate large amounts of data and make predictions, AI methods hold the potential to revolutionize human healthcare, helping to better prevent, diagnose, and treat diseases. As AI-integrated technologies move from the research lab to clinical spaces with real human patients, expert medical input and human observation remain necessary, especially for complex or ambiguous health cases. The introduction of AI into this vital area of science highlights the strength of a combination of human insight and computer vision to see more clearly. In what other ways has AI intersected with the medical world?

HARNESSING MOLECULAR POWER

Nature was humanity’s first pharmacy. Some of the oldest records of natural products, useful substances that we gather from other living things, are almost as old as the beginning of written records themselves. Aspirin, opium, penicillin—some of the first widespread and effective painkillers and antibiotics—were produced by plants and microbes. Our need to discover new useful molecules has only accelerated, driven by an ongoing arms race with infectious disease and a vast expansion of industry. Our society sends scientists on a perpetual hunt for new useful molecules from any source that will yield them.

This search takes two major directions that are simple to state but difficult to do: make a new substance from scratch or discover it in nature. Researchers can design new molecules, using previously known principles or an already known molecule as a starting point. Or they can isolate compounds from the great diversity of organisms around us and screen them for a specific useful property. Either approach is a gamble: a large amount of time, money, and effort may yield a single useful substance, or none at all. For both approaches, researchers have turned to machine learning to improve the odds.

One example of this comes from research on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and similar infectious bacteria, whose cell walls cannot be penetrated by many traditional antibiotics. Researchers in Paul Hergenrother’sprofessor of chemistry (ACPP leader/MMG) group turned to machine learning to help them identify principles for designing new antibiotics to treat these infections. After testing hundreds of different types of chemical compounds against P. aeruginosa, they determined favorable chemical traits for potential drugs to more readily cross the cell wall and accumulate in the bacteria.

Other researchers carried the principle of training computers using data from naturally occurring molecules even further. Huimin Zhaoprofessor of chemical and biomolecular engineering trained a machine learning algorithm that predicts the functions of enzymes, proteins that catalyze reactions within cells, from their sequences. More recently, Zhao and his collaborators developed another deep learning algorithm that predicts the enzyme substrate specificity. These AI tools are highly useful for enzyme catalysis, synthetic biology, and natural product researarch. For example, they lent credibility to a shortcut in natural product discovery: before screening molecules, scan genomes for genes encoding likely-looking proteins, those that might have desired functions themselves or help produce other compounds that do. They also gave researchers a new way to improve their odds at picking the right target to aim for when designing a useful molecule from scratch.

However new molecules are designed or discovered, there must be a way to make them, eventually on industrial scales, for practical human use. Natural products are often large and complex molecules, and those that are not protein-based lack clear, consistent building blocks. One way to solve this problem is by employing the biosynthetic prowess of nature’s chemists. Bacteria and other microbes have specialized genes and machinery for building chemically intricate natural products. These biosynthetic pathways can be hacked for making desired molecules. In 2019, researchers from Zhao’s lab demonstrated how BioAutomata, the AI system integrated into the iBioFAB, drove the microbial production of lycopene, a red pigment in found in tomatoes. Through iterative cycles, BioAutomata learned how to do this without human oversight in weeks, reducing the. time and cost of typical microbial engineering.

Martin Burkeprofessor of chemistry (MMG) took a different approach for automating molecular synthesis. In the early 2000s, his group began envisioning how machines could do modular chemical synthesis. His team developed a novel approach inspired by the Lego-like building of nucleic acids and proteins. They created a chemical “language,” one that AI can readily learn to speak, of molecular building blocks, pairing this system with automated laboratory machinery that can assemble those building blocks as directed.

Only a couple of years later, a related team from the Molecule Maker Lab Institute developed a method called “closed-loop transfer,” in which their AI algorithm predicts what types of molecules might be best for a particular task, then (in partnership with the modular chemistry system) supports their synthesis and tests of their actual function. Data from these functional tests feed back into the model, refining its ideas for the next round of synthesis and testing. Using this method, the team identified promising new compounds for a new generation of solar panel technology.

“What AI allowed us to do was to very strategically sample that huge haystack with the experiments from which we would learn the most. So it does what's called uncertainty minimization, via prioritizing for learning potential . . . the AI fails on purpose . . . The reason it's doing that is that collectively those results help minimize its own uncertainty about how to predict whatever it is you care about.”

—Martin Burke (MMG)

professor of chemistry

Perhaps most important, Burke’s team found a way to confer with their AI tool, breaking open its metaphorical black box and extracting the insights it gained through its iterative cycles. As we enter the new era of AI in genomics, this type of direct engagement between human and computer, with each partner playing to respective strengths, is indispensable.

What is AI Today?

Definitions have changed and diversified over time and across fields, but with a few common threads holding them all together. How do researchers from across the breadth of genomics view AI?

“If I'm talking with researchers about AI-based techniques, what we're thinking about is a very specific offshoot of statistics that is designed to deal with large or complex data, an approach that is not based on the traditional frequentist statistics.”

—Becky Smith (IGOH co-leader/CGD)

professor of veterinary clinical medicine

“The development of these deep learning tools . . . particularly the large language models, AI probably is a more appropriate word than just machine learning. It is able to generate a new hypothesis and reasoning. Not just to fit in the data but to generate, to expand the results.”

—Huimin Zhao (BSD leader/CAMBERS/CGD/MMG)

professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering

“AI is a little bit of everything, spiced up with data sets that may be present in one area, but not so present in the other. They’re now nicely expanded and include data from so many different domains that there is sort of this feeling of universality in terms of what you can do.”

—Olgica Milenkovic (CAIM co-leader/BSD/CGD/GNDP)

professor of electrical and computer engineering

“AI is really not intelligence; it's in a way a misleading term. What you are doing is creating a big network that is very powerful in interpolating in a very high dimensional space . . . and because nowadays of the size of this network, you can really put a lot of knowledge inside this big black box. That makes it powerful, because it's able to find interesting connections among all the inputs that you provide.”

—Mattia Gazzola (M-CELS)

professor of mechanical science and engineering

“You can start to learn very complicated patterns that you couldn't learn with smaller amounts of data. It's a difference in scale—but at some point, that becomes a difference in degree. So it's a quantitative difference until there's a sort of a phase transition and then you get a qualitative difference.”

—Dave Zhao (GNDP)

professor of statistics

“In my view, AI is trying to do things like humans would normally do that require some intelligence . . . it has to be a tool that has some analytical, practical or creative intelligence, such as for problem solving, critical thinking, observing the world, or creating new hypotheses.”

—Heng Ji (BSD/CAMBERS)

professor of computer science

What does AI mean for science?

The scientific world stands at a crossroads with AI; some applications will lead to new ways of understanding biology, while others will dead-end in undelivered promise and societal costs. As researchers forge ahead, AI’s capabilities and drawbacks elicit strong, simultaneous, and conflicting reactions.

The possibilities offered by AI are exciting. IGB members see the potential to explore questions that were previously intractable. AI can feel like alchemy, transforming raw data into polished predictions of molecular structures, gene functions, or disease outcomes.

New avenues opened by AI offer hope to solve big problems. We are facing huge challenges as a society, including a changing climate, emerging infectious diseases, and global food insecurity. AI’s multitude of applications hold promise to transform the solution space for a wide array of problems.

Overstatement of AI’s strengths and minimization of its weaknesses cause concern. While AI is framed as replicating human intelligence, researchers worry that it may be used in contexts where its inability to effectively critique itself or attach human value to its conclusions will impede rigorous and responsible science.

There is pressure to keep up with the forefront of a quickly moving field. AI has become a priority for many different organizational bodies within the research world. Scientists feel tension between the benefits of exploring a powerful tool and costs of mis-implementation.

“Two of the most important things we need to be doing now to increase the likelihood of having positive benefits are being explicit and honest about how our teams are using these tools, and creating opportunities for critical discussion on our teams to reflect upon how we can use AI ethically to facilitate the ongoing practice of scientific discovery.”

—Will Barley

professor of communication

Led by groups such as the Center for Artificial Intelligence and Modeling research theme and the institute’s computational genomics office, the IGB community is considering how we can draw on our strengths to navigate the intersection of AI and genomic research. IGB's culture of interdisciplinarity is helping its members to integrate the computational, statistical, engineering, and biological skill sets that form the foundation of AI innovation in genomics. This team science approach will strengthen the development of science-specific AI methodologies, while the teams themselves continue to be grounded in the IGB’s tradition of supporting collaboration with co-location and person-to-person communication. What new directions is AI enabling?

INTELLIGENCE RECONSTRUCTED

Constructing models of living systems is a necessary tool of biology; now, AI is becoming a key approach in model construction. When is it the right choice? And could interrogating an AI-constructed model sometimes be more useful than interrogating a living system?

Although every biological system contains layers of complexity, we have been able to construct surprisingly simple models to describe many natural phenomena. The vertebrate heart can be understood as a pump connected to a series of tubes. The central dynamics of evolution were difficult to a discern against the background of a creationist conceptual framework, but once grasped, simple enough to lay out with pen and paper.

In contrast, biological “final frontiers”—the brain, the immune system, the genome, the microbiome—have remained a challenge in part because any adequate model would require the integration of too many dynamically related variables for a verbal or human-constructed mathematical model to accommodate. AI, with its insatiable appetite for data and its aptitude for discerning patterns, feels like an inevitable part of the way forward.

“AI technologies can predict, they can reveal patterns you didn't know before. They can automate. The strength of AI is to allow you to ask questions you didn't know you could ask before, to broaden your concept of what science can look like in your field.”

—Dave Zhao (GNDP)

professor of statistics

Nearly impenetrable complexity can be found even within each living cell. As a cell grows and divides, it contains an incomprehensible but coordinated dance of proteins, DNA, salts, and other molecules of life. That is, incomprehensible to us—but as a team led by Zan Luthey-Schultenprofessor of chemistry and including Ido Goldingprofessor of physics (CAIM/IGOH) and Angad Mehtaprofessor of chemistry (MMG) has shown, comprehensible to AI. In 2023, they and their colleagues received funding from the NSF to model the complete, molecular-level functioning of a “minimal” cell. Just two years later, their AI-powered model cell grows, replicates its DNA, and divides into two distinct daughter cells.

What is an in silico cell good for? As models like these continue to improve, researchers hope to use them in place of living systems to test responses to perturbations or outcomes to engineering approaches. Synthetic biologists, aiming to develop microbial strains making more or better natural products, could try out different genetic constructs on a virtual cell. They could save the more expensive genome editing process only for the most promising DNA sequences they might try to insert. AI, in this context, could save time and money by directing empirical validation, but it could not replace it.

“How do you come up with representations of complicated biological data? So I think these large language models for biological data have been pretty useful because they take either text or they take DNA sequences, or they take protein sequences and they convert them into numerical representations that you can then use for various applications . . . But still in biology there is always this big issue of how do you verify the validity of your results?”

—Olgica Milenkovic (CAIM co-leader/BSD/CGD/GNDP)

professor of electrical and computer engineering

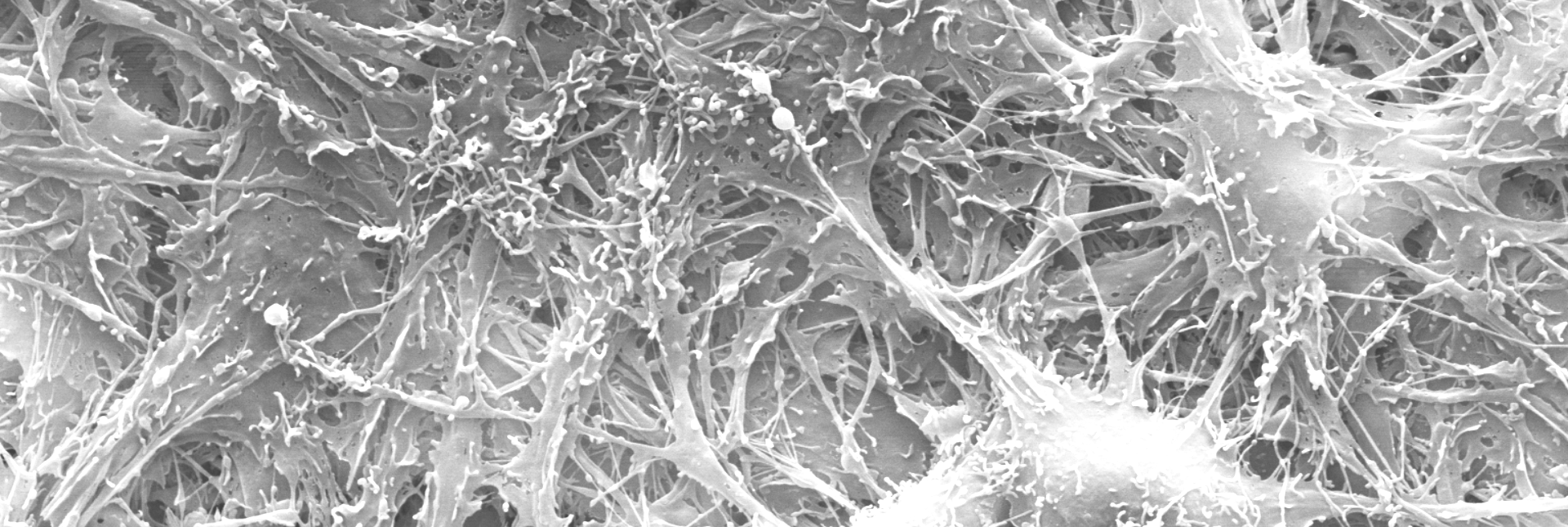

It is almost a truism to say that we cannot move away from living systems as we try to understand them. Our journey to develop AI began with neuroscientists modeling neurons; our journey into numbers leads us right back to living cells. Fundamental research by Mattia Gazzolaprofessor of mechanical science and engineering (M-CELS), Hyun Joon Kongprofessor of chemical and biomolecular engineering (M-CELS leader/EIRH/RBTE) and their colleagues in the Mind in Vitro project is balanced between these two realms. They are using AI as a tool to test aspects of constructing a living computational device, an engineered circuit populated with living neurons. The neurons grow, connect and fire on specially designed substrates, an automated system that helps to support the neurons and monitor their electrical activity. AI helps them to make sense of how the neurons connect to each other and how they send and respond to electrical signals.

Mind in Vitro research doesn’t exactly bring AI research full circle; instead, it feels like a moment when in a technological spiral toward a goal of engineered intelligence, the point of progress stands above the starting point. Neural networks mimicked living circuits, and now living circuits outside the brain are monitored and refined by the next generation of such computational networks. Which one will eventually produce a human-built system that we recognize as a truly flexible and universal intelligence? Maybe both; maybe neither. But in the pursuit, we are learning a great deal.

How we move forward

THE WORLD IN A BLACK BOX

Science cannot build us a time machine, but it can give us a glimpse of the future. Our global community faces numerous challenges: to our food supply, to our health, to the environment. Plotting a mathematical course for how multiple intersecting threats might play out gives us a way to innovate and prioritize solutions. The predictive capabilities of AI are a powerful tool for constructing an understanding of what the future might hold.

Prediction lies at the heart of AI’s capabilities. As it finds patterns in incredible amounts of data, the models it builds can project the next piece of the pattern: the measurement or outcome that might come next. When tackling a challenge like how to feed a growing world population, AI is increasingly useful to shape the input to these models in addition to the output.

Andrew Leakey’sProfessor of plant biology (CAMBERS leader/PFS) lab group has continued to leverage AI in pursuit of food and fuel security. To further streamline data collection on experimental crops, they are using generative adversarial networks—a pair of models that work together, one creating output and the other testing it—to create a system that can learn to recognize plant features from a much smaller training data set. They are also learning to ask AI what else it can easily see that a human researcher cannot, such as the precise spatial arrangement of stomata on a leaf.

The plant phenotype data generated by approaches like these will be fed into models such as one being developed by a group led by Alex Lipkaprofessor of crop sciences (CAIM/GEGC/IGOH). This model, powered by AI, will take genotype to phenotype prediction to another level, one that considers the functional relationships among genes in a way that decades of traditional genetics could not; access to this quality of prediction will support more successful crop breeding. Similarly, a NSF Global Center led by Leakey and Tracy Lawsonprofessor of plant biology (CAMBERS/PFS) will rely on AI predictive modeling to support the innovation of water-efficient, high-yield crops.

“For biology, you have the central dogma already describing the information flow, and a lot of data you can also collect at a large scale with all the genomics tools. Of all the scientific domains, probably biologists are the best positioned to take advantage of AI . . . Another big advantage of biology has is the evolutionary history, because that is not something that any other discipline has.”

—Huimin Zhao (BSD leader/CAMBERS/CGD/MMG)

professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering

AI is poised to bring a new level of understanding to the flow of information that the central dogma describes, connecting genotype through the sequence of DNA to the structure of proteins that help construct phenotype. Key to the genotype-phenotype relationship is also the prediction of how the environment prompts the cell to produce some proteins and inhibits the synthesis of others. Sergei Maslov’sProfessor of bioengineering (CAIM co-leader) group has tackled this question with the creation of a model called FUNgal PRomoter to cOndition-Specific Expression, or FUN-PROSE.

The FUN-PROSE model uses AI to predict how genes in baker’s yeast, along with two less well-known fungal species, react to environmental changes. Maslov’s group determined that their model was able to accurately predict the activity of more than 4000 genes in dozens of different environmental conditions, and were able to query the model about what features of DNA sequence it used to make those predictions. The model struggles to work with DNA sequences it has not encountered before, however, and will need new features and new data to learn from to expand its capabilities to other species.

This is a good reminder that even the most sophisticated AI algorithm is only as reliable as the quality of data it is trained on and validated with. The need for rigorous, real-world experiments remains: an AI weather model cannot know if it is actually raining, but we can tell the moment we step our physical bodies outside. AI can help us predict the world as it may be, as well as which steps we take might bring us closer to the world we want. Ultimately, it is reality that we will keep living with.

BETTER LIVING THROUGH DATA

Genomics has revolutionized medicine. Querying the DNA of a human patient or the possible pathogenic microbes inside them provides a seemingly unbiased and objective view of possible sources of illness. Genomic medical research has built repositories of DNA sequence: individual genomes, tumor genomes, even the genomes of individual cells within tumors; this information is combined with data on symptoms, responses to therapeutic interventions, and outcomes. These vast data sets are potent fuel for the engine of AI, which is now moving to the forefront of the health research revolution begun by genomics.

Personalized medicine is an emerging practice that genomics and AI together can help realize. In efforts to move away from “one size fits all” approaches, researchers and clinicians are examining ways to tailor medical care to the individual. For example, rather than prescribing a therapeutic and waiting to see if it works, personalized medicine probes a person’s genomic and diagnostic information to inform treatments with the highest probability of effectiveness.

While this is a promising future, it relies on synthesizing volumes of data to bring it to fruition—both each patient's individual data sets, as well as trends across hundreds of different patients. Human researchers searching for patterns in data is nothing new; it is a fundamental aspect of science. A particular strength of AI, however, is its ability to represent complexity and uncertainty with numbers.

“The nature of the problem is so complicated because humans have so much heterogeneity, which is to say we are different from each other in terms of the relative amounts of molecules you will find in a clinical sample. To make predictions of anything using biomarkers, it's pretty complex. The AI models can make predictions that come with a level of statistical certainty . . . It's almost like quantum mechanics. Rather than a biological state being clearly classified into state A and state B, there are many possible states in between. That's where AI has the ability to interpret and make predictions with complex information.”

—Brian Cunningham (CGD leader)

professor of electrical and computer engineering

Current work in the Center for Genomic Diagnostics remains largely focused on innovating new diagnostic technology, as well as identifying new biomarkers to help indicate disease states. This work is aided by scientists with computational or engineering backgrounds who have already begun using machine learning and AI tools to make sense of many types of health and disease data. They are also working to make these types of analyses accessible to others.

Mohammed El-KebirProfessor of computer science (CAIM/IGOH) and his team, for example, develop custom machine learning models for other researchers to apply for cancer genomics. Their PhySigs software identifies patterns of mutations in sequencing data to better understand a cancer’s evolutionary history. MACHINA, on the other hand, helps tracks how tumors migrate by comparing sequences from the primary tumor and metastatic sites. These AI tools come into play after data collection, ready to find new patterns in cancer data. This is especially beneficial for predicting responses to different treatment and future tumor evolution.

In another major health challenge—the fight against infectious disease—tools being developed by professor of veterinary clinical medicine Becky Smith (IGOH co-leader/CGD) and collaborators promise to help public health officials and healthcare providers respond proactively to the detection of pathogens. Using data from mosquito monitoring traps on the presence of West Nile Virus, an AI-powered predictive model could flag the location of a likely future outbreak, allowing mitigation to begin before illness spreads. Working in collaboration with Argonne National Laboratory and the Illinois Department of Public Health, members of her team are also working on ways to predict the appearance of new multidrug-resistant infectious bacteria.

Despite AI’s incredible facility for modeling and prediction, it would be a mistake to think it infallible. AI models are only as reliable and objective as the data and assumptions that are built into it; and because they typically are constructed as “black boxes,” how they arrive at their conclusions is both important and difficult to verify.

“One of the biggest challenges with AI is that it detects relationships that are there for a reason that are not biological. If a model is not a black box, I can look at it and say, oh, that's not a biological relationship. I can tell you why that relationship is there. It's not something we want in our model going forward . . . Whenever I work with people who are doing AI models, I insist that we break open the box.”

—Becky Smith (IGOH co-leader/CGD)

professor of veterinary clinical medicine

There are multifold advantages to examining the “inner workings” of AI algorithms in this way. In addition to providing an avenue for double-checking its analyses, we can interpret and gain new insight from the patterns it identifies. While a revolutionary tool, AI’s limitations reinforce rather than remove the basic tenets of sound science: check your assumptions, validate your results, and retain ethical responsibility for how data are gathered, stored, and used. These efforts help balance the approaches we choose and can further potentially life-saving innovations in medicine.

MOVING FORWARD, TOGETHER

Modern science contains an organizational juxtaposition. As our knowledge grows, fields have fractured into increasingly specific subdisciplines. But as scientists seek to tackle grand societal challenges, collaboration becomes a necessity for addressing these complex research questions. The IGB creates a space for productive team science, providing infrastructure to help tear down disciplinary silos and promote crosstalk between researchers. How do these teams work together to advance genomics and AI? How might AI’s role in team science evolve?

Historically, AI research has focused on the technological innovation of its fundamental capabilities. AI for science is a bourgeoning subfield that instead prioritizes developing new AI platforms for particular scientific applications. To achieve this, collaboration is key. Computer scientists and engineers can build AI tools optimized for particular research purposes; physical and life scientists ensure that these technological advances are grounded in the physical world and address current research needs.

One example of AI for science in action is a collaboration between the Center for Artificial Intelligence and Modeling and AbbVie. As a pharmaceutical company, AbbVie is interested in implementing AI in the drug design and discovery pipeline for tasks such as understanding and predicting the properties of therapeutic drug candidates. Some of these include a potential drug molecule’s absorption, as well as its biological target and side effects. Led by Olgica Milenkovicprofessor of electrical and computer engineering (CAIM co-leader/BSD/CGD/GNDP) and Sergei Maslovprofessor of bioengineering (CAIM co-leader), IGB researchers are guiding the development and application of AI tools like graph neural networks for these purposes and others.

Interdisciplinary efforts in the Mining for anti-infectious Molecules from Genomes theme aim to improve large language models that predict the structure and function of a class of natural products called lasso peptides. These molecules represent a promising avenue for new therapeutics due to their unique knot-like structure and diverse biological applications, but current protein language models lack the specificity to make accurate predictions for lasso peptides. Vanderbilt University professor of biochemistry Doug Mitchell’s group used their bioinformatic and laboratory expertise to identify lasso peptide sequences in microorganisms' genomes and manually validate any new sequences they discovered. Researchers in Diwakar Shukla’sprofessor of chemical and biomolecular engineering (CAMBERS/MMG) lab then used this information to develop LassoESM, a lasso peptide-tailored protein language model.

“We learned the language of those lasso peptides using masked language modeling, which is where you hide part of the peptide, and then you try to predict the other half. Once you have learned the language of how the lasso structure is formed in nature, then you can train efficient property prediction models based on these language model parameters.”

—Diwakar Shukla (CAMBERS/MMG)

professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering

As new algorithms continue to enable better prediction, pattern recognition, and analysis, researchers are also examining how AI can become a better collaborator—not only extracting information from data sets but also generating new knowledge and hypotheses. Generative AI is a step towards this. One such example of this comes from Huimin Zhao’sprofessor of chemical and biomolecular engineering (BSD leader/CAMBERS/CGD/MMG) lab, where the team used an unsupervised deep learning framework called a variational autoencoder to generate new mitochondrial targeting sequences. These short peptides are like mailing addresses that tag proteins to be sent to mitochondria and have previously been difficult to design. Their generative AI was able to suggest a million different sequences, and a subset were experimentally validated and proven successful, opening the door to new biological studies.

Current work at the Molecule Maker Lab Institute also seeks to improve the reasoning and creativity of AI. In a project led by Heng Jiprofessor of computer science (BSD/CAMBERS), an Illinois research team including Martin Burkeprofessor of chemistry (MMG), Ge Liuprofessor of computer science (BSD/CAMBERS/MMG), Hao Pengprofessor of computer science, and Ying Diao have created a large language model called mCLM that can “speak” two languages at once. The model uses the language of chemistry to discern relationships between molecular structure and function and then translates these to human language to reveal new potential therapeutic drug candidates. The team assessed this new AI paradigm by rescuing “fallen angels,” drugs that failed in the final stage of clinical trials. Their model’s critical thinking capabilities helped identify why the drugs failed and improve those functions.

Synergies between AI and robotics also offer the possibility of fully autonomous laboratory systems. Researchers see a pathway to integrate many of the different capabilities of AI with next generation robotics to produce facilities that could help design and run experiments, analyze data, identify and execute follow-up analyses. A long-term goal of MMLI is to build a human-in-the-loop autonomous laboratory—complete with AI agents capable of critical thinking, robots to carry out tasks, and human oversight—to design and make new molecules.

IGB members are also implementing these ideas to advance synthetic biology research in the iBioFoundry, with projects focused on developing more nutritious animal feeds, resilient crop varieties, and enzymes capable of degrading plastics. Ji, Zhao, and Liu are currently working in the CAMBERS theme on developing advanced bioengineering foundational models for these purposes. As these tools mature, they will enhance rather than replace human creativity, accelerating discovery and enabling researchers to tackle problems once thought out of reach.

“There are a lot of really complicated problems that humans cannot easily solve because the search space is so huge. Our memory is limited, so we can never consider all the possible combinations and optimizations, but the AI can do that. So, it's not trying to replace any human labor, but rather serve as a companion for the human scientist.”

—Heng Ji (BSD/CAMBERS)

professor of computer science

MOVING FORWARD WITH AI

AI may have changed the game, but it has not changed the fundamentals of sound science. As we grapple with how to use AI wisely, what do IGB members feel the community needs most?

A grounding in methods underlying AI development

Even to experts in their fields, AI can feel like a black box. Multiple IGB members agreed that comfort with the statistical principles upon which AI is built are key to applying it fluently.

Team science-based approaches to AI research

There is a language barrier between life science researchers and AI experts. Strategies for clear communication must be prioritized to support the application of AI to genomic research.

Data sets that are curated for AI’s strengths

AI can accommodate large and complex data sets, but they must be cataloged consistently and systematically, including negative findings that typically go unpublished.

A continued rigor in empirical work

AI is prone to hallucinate, as well as to accentuate biases that existed in the data it was trained on. This places, if anything, an increased value on the human capability to perform ground truth validation.

Recognition of the limitations of AI

IGB members agreed that for all its ability to mimic human intelligence, current AI can neither think nor supply human meaning for its outputs. We must retain our responsibility to decide why data are important or produce hypotheses that may spark the next scientific revolution.

“The optimistic future for AI is when it helps us to speed up or to better learn how to answer the why questions, and that would be done in combination with traditional learning and experimentation. . . Experiments are slow and expensive, but they are the ground truth. No AI should be taken at face value.”

—Sergei Maslov (CAIM co-leader)

professor of bioengineering

“AI offers tools to democratize knowledge and tackle global challenges like poverty and disease. I hope we are guided by the best of human values when using these tools.”

—Diwakar Shukla (CAMBERS/MMG)

professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering

“As scientists, what people try to do is get meaning from data. And AI cannot give you meaning because data cannot give you meaning . . . that is something that is uniquely human.”

—Dave Zhao (GNDP)

professor of statistics

BIOMARKER 19

Writers: Katie Brady, Claudia Lutz; Designer: Isaac Mitchell; Developer: Gabriel Horton; Managing Editor: Nicholas Vasi

PHOTO CREDITS

Marc-Élie Adaïmé, Andrew Leakey Lab, Jim Baltz, Beckman Imaging Technology Group, Claire Benjamin, CUH2A, Umnia Doha, Andrew Dou, Micheal Dziedzic, Scott Gable, Mattia Gazzola, Heather Gillett, Andrew Gleason, Don Hamerman, Hee-Sun Han Lab, Heng Ji, Darrell Hoemann, National Human Genome Research Institute, Vanessa Noboa, Craig Pessman, Heidi Peters, Rhanor Gillette Lab, L. Brian Stauffer, Stephen Boppart Lab, Mikhail Voloshin, Jiayang (Kevin) Xie, Hongbo Yuan, Fred Zwicky

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The writers thank these individuals for their invaluable contributions to the scientific content of this piece:

Will Barley, professor of communication

Martin Burke, professor of chemistry (MMG)

Brian Cunningham, professor of electrical and computer engineering (CGD leader)

Heng Ji, professor of computer science (BSD/CAMBERS)

Mattia Gazzola, professor of mechanical science and engineering (M-CELS)

Andrew Leakey, professor of plant biology (CAMBERS leader/PFS)

Sergei Maslov, professor of bioengineering (CAIM co-leader)

Olgica Milenkovic, professor of electrical and computer engineering (CAIM co-leader/BSD/CGD/GNDP)

Jacob Sherkow, professor of law (GSP)

Diwakar Shukla, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering (CAMBERS/MMG)

Rebecca Smith, professor of veterinary clinical medicine (IGOH co-leader/CGD)

Dave Zhao, professor of statistics (GNDP)

Huimin Zhao, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering (BSD leader/CAMBERS/CGD/MMG)

Thank you to the writers and units whose work we referenced in the development of this piece:

Megan Allen, Cancer Center at Illinois, Phil Ciciora, Jonathan King, Alisa King-Klemperer, Jenna Kurtzweil, Shelby Lawson, Ryann Monahan, Ananya Sen, Samantha Jones Toal, Liz Ahlberg Touchstone, Diana Yates, Lois Yoksoulian