New funding offers a path to a breakthrough in affordable, accessible viral testing

The proposed viral testing method will be developed for fast, easy and affordable use by healthcare providers at community testing centers.

In medicine, knowledge leads to the power to heal. For some infectious diseases, timely detection makes the difference between the chance for restored health and illness that progresses and spreads to others. A new R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health to researchers at the University of Illinois and their collaborators, “Human factors-designed triple test for HIV, HBV, and HCV infection in whole blood using target amplification, signal amplification, and crumpled graphene biosensor readout,” aims to lower the barriers of testing for three significant but treatable illnesses.

Electrical and computer engineering professor Brian Cunningham, bioengineering professor Enrique Valera Cano, and Dean of the Grainger College of Engineering Rashid Bashir (CGD/M-CELS) are principal investigators in the effort to develop an inexpensive, portable, and rapid test that detects the presence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C viral fragments in a small blood sample. Valera Cano and Bashir are members and Cunningham the leader of the Center for Genomic Diagnostics at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology. SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University infectious diseases professor Sabina Hirshfield is also a co-PI.

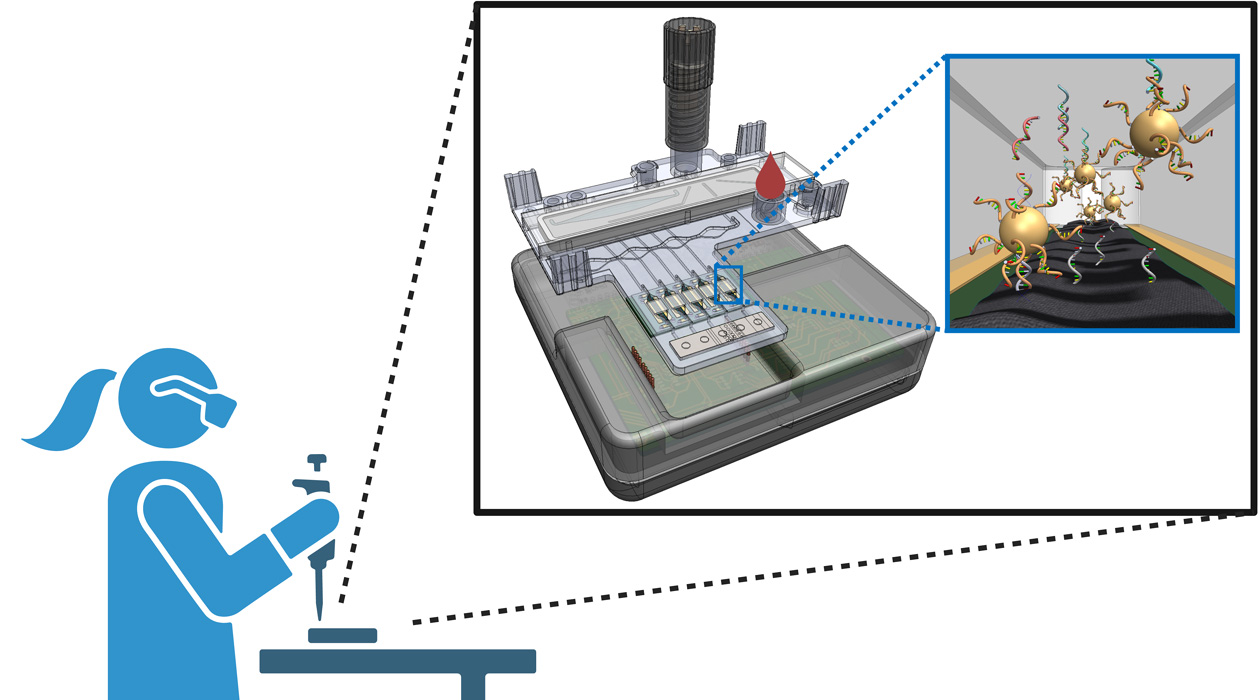

The project team’s aim is to develop a holistic testing system that will include a sample pre-processing component, a sensor, and a user interface. Valera Cano, Bashir, and Cunningham will orchestrate development of the processing cartridge and sensor, while Hirshfield and Karine Dube, an infectious diseases and global public health professor at the University of California San Diego, will work to ensure that the system’s design enables care providers to easily use the device and interpret results.

“We have two specialists in human factors engineering to inform the design by querying real people who would use a device like this, not only at the early stage, but also to give us feedback during the iterative phase where we're building different versions of the device and moving towards the final product,” Cunningham said. “We want to end up with a device that people would use in the real world, by taking feedback from people that are knowledgeable about the field of human factors engineering.”

Also joining the effort are mechanical science and engineering professor Bill King, biochemistry professor Nicholas Wu (IGOH/MMG), and Carle Illinois and Carle Foundation Hospital clinical sciences professors James Kumar and Karen White. Four graduate students are rounding out the team.

The past few years have seen the development of various less costly, more portable tests for infectious diseases. The team chose to focus on these three viruses—HIV, HBV, and HCV—because they frequently co-occur and because early diagnosis can open up the best treatment options. Timely testing also enables individuals to take steps to prevent transmission of the diseases they cause.

“One of the things that we're trying to do here is develop a portable device that can be used out of centralized labs,” Valera Cano said. “That gives a new opportunity to the people actually infected with these viruses to go to places which are stigma free, so that there is a more friendly way to receive a test of these kinds of viruses.”

In the last few years, the public has become familiar with two ways of diagnosing a viral illness: rapid antigen tests and PCR tests. The former, exemplified by home covid and flu tests, are fast and affordable, but poor at detecting small concentrations of viruses. The latter, in which samples are processed in a laboratory to make copies of select fragments of viral genetic material, can detect even small concentrations of viruses, but are more expensive and relatively slower.

The team’s approach to viral detection aims to combine the speed and portability of rapid antigen tests with the sensitivity and accuracy of PCR tests. Its specificity is built on the same technology as CRISPR gene editing: a molecule that is designed to recognize and stick to specific viral genetic material, which in this device will release a large number of gold nanoparticles that will be used for virus detection.

“We proposed a method that utilizes the CRISPR/Cas technology that many people know about for genome editing. We're adapting it for virus detection,” Cunningham said. “It’s a novel assay method that can overcome the limitations of PCR, combined with a novel sensing approach."

These methods are well-suited to the challenge of detecting multiple viruses simultaneously, each with multiple strains. The team already has expertise with the technologies involved, and will focus on scaling and integrating them, making sure they work quickly and accurately with the amount of blood obtained from a simple finger stick—all while making sure the resulting device can be made affordable.

“I think one of the bigger challenges is the integration of all these components—the biological assay, the electronic readout in a microfluidic cartridge,” Valera Cano said. “This is a very exciting challenge because it's also unique. And we expect to have a very high impact when we are able to deliver this kind of device.”

To keep the device inexpensive and portable, the team will leverage 3D printing to produce the cartridges and explore ways to integrate smart phone camera technologies to read the device output.

"I'm very excited about the scale of project taking place across the campus, and about this one in particular," Bashir said. "We have amazing opportunities to create new partnerships, which allows us to bring the depth of our expertise in bioengineering and medicine to this transformative type of effort."