The IGB’s Art of Science program is a celebration of common ground between science and art. Each exhibit comprises images from IGB’s research portfolio, enhanced to highlight the beauty and fascination encountered daily in scientific endeavors.

Read More About Art of Science

Analog Wine Library 129 N Race St. Urbana, IL

Scientist Collaborator

Sarah Asif and Yujin Ahn

Instrument

Zeiss LSM900 confocal microscope

Funding Agency

Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Chicago

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Sarah Asif and Yujin Ahn

Instrument

Zeiss LSM900 confocal microscope

Funding Agency

Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Chicago

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Adriana Andrus

Instrument

Nanozoomer Slider Scanner

Funding Agency

National Institutes of Health

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Abby Weber, Joey Czarnik, Manny Lu, Jessica Nunge, Leslie Escamilla, and Zoe Zemanek

Instrument

Stereomicroscope and FEI Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope

Funding Agency

National Science Foundation

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Umnia Doha

Instrument

Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan

Funding Agency

Cancer Center at Illinois

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Umnia Doha

Instrument

Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan

Funding Agency

Cancer Center at Illinois

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Hongbo Yuan, Andrew Dou, Gaurav Upadhyay, Zhantao Song, Xiaotian Zhang, Seung Hyun Kim, and Kimia Kazemi

Instrument

Scanning Electron Microscope

Funding Agency

University of Illinois and the National Science Foundation

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Yanyu Xiong, Lifeng Zhou, and Xing Wang

Instrument

Zeiss 710 Confocal Microscope

Funding Agency

National Institutes of Health and the Cancer Center at Illinois

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

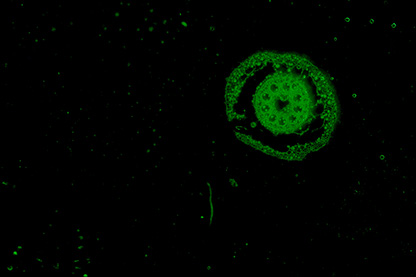

Scientist Collaborator

Snigdha Mathure

Instrument

Zeiss LSM900 Confocal Microscope

Funding Agency

National Institute of Health

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Snigdha Mathure

Instrument

Zeiss LSM900 Confocal Microscope

Funding Agency

National Institute of Health

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

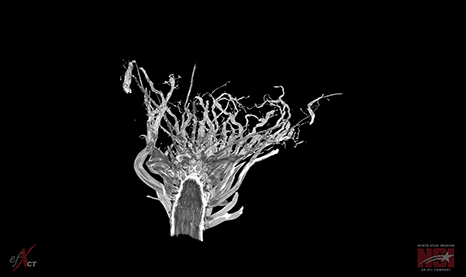

Scientist Collaborator

Sam Walker and Scott McCoy

Instrument

X-Ray CT Scanner

Funding Agency

The Center for Advanced Bioenergy and Bioproducts Innovation

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Sam Walker and Scott McCoy

Instrument

X-Ray CT Scanner

Funding Agency

The Center for Advanced Bioenergy and Bioproducts Innovation

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

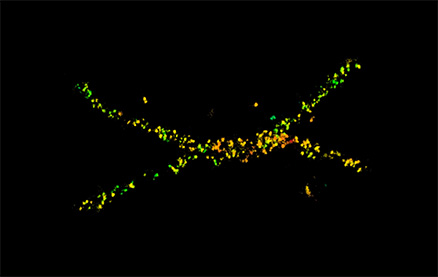

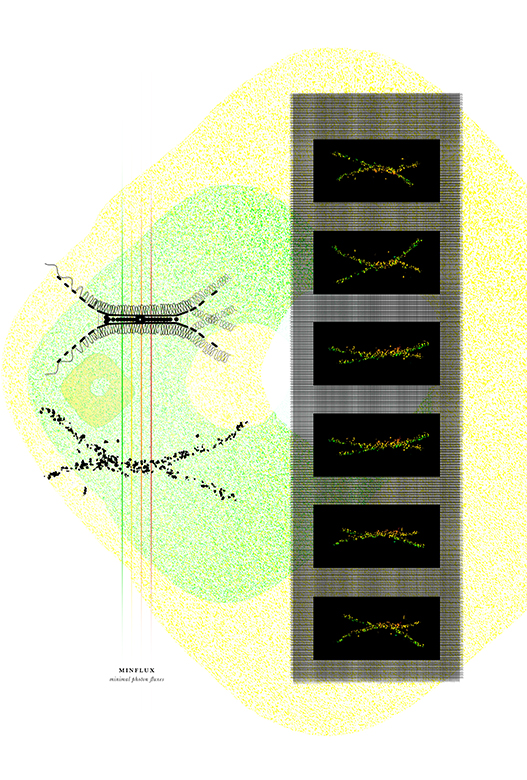

Scientist Collaborator

Reza Rajabi Toustani and Sasha Kakkassery

Instrument

Minimal Fluorescence Photon Fluxes Microscopy (MINFLUX)

Funding Agency

National Institutes of Health

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Reza Rajabi Toustani and Sasha Kakkassery

Instrument

Minimal Fluorescence Photon Fluxes Microscopy (MINFLUX)

Funding Agency

National Institutes of Health

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

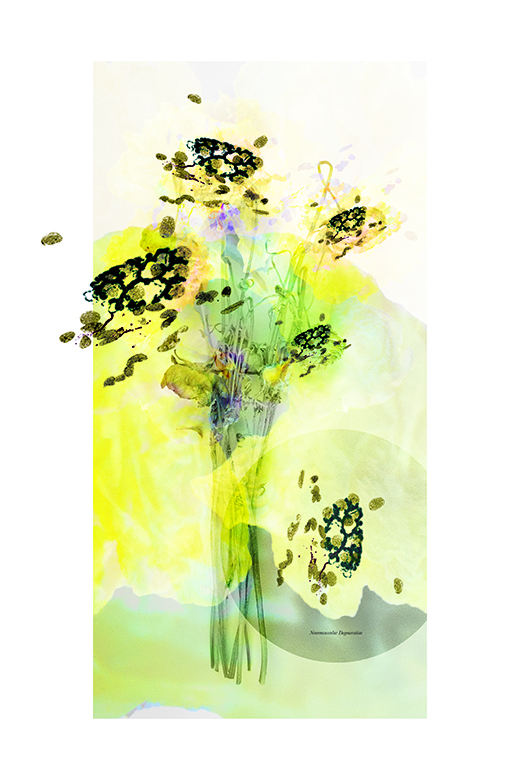

Scientist Collaborator

Sofia Gonzalez, Martin Bohn, Michelle Wander, and Miranda O’Dell

Instrument

Zeiss Axio Zoom.V16

Funding Agency

The U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

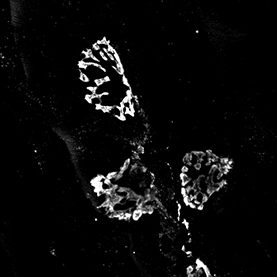

Between thought and action lies a physical structure: the neuromuscular junction. Our body is filled with these microscopic sites of intersection, the places where the nerve cells, or neurons, make contact with muscle fibers. Without the signals sent by nerves, muscles cannot make organized, intentional movements; as the normal functioning of these connection points declines with age, muscle loss and impaired movement follows. Most knowledge of age-related changes in the neuromuscular junction come from the study of male animals, yet the female aging process is known to differ. New research seeks to close this knowledge gap to better support women’s strength in aging.

This pair of images shows neuromuscular junctions, their branching structures captured under the microscope in an effort to document how aging and sex interact to impact their function. Their shapes have been reimagined as blossoms that were once full of vigor but have faded and weakened with time and lack of care. Science cannot reverse the effects of time, but can make care in aging more equitable and effective.

Between thought and action lies a physical structure: the neuromuscular junction. Our body is filled with these microscopic sites of intersection, the places where the nerve cells, or neurons, make contact with muscle fibers. Without the signals sent by nerves, muscles cannot make organized, intentional movements; as the normal functioning of these connection points declines with age, muscle loss and impaired movement follows. Most knowledge of age-related changes in the neuromuscular junction come from the study of male animals, yet the female aging process is known to differ. New research seeks to close this knowledge gap to better support women’s strength in aging.

This pair of images shows neuromuscular junctions, their branching structures captured under the microscope in an effort to document how aging and sex interact to impact their function. Their shapes have been reimagined as blossoms that were once full of vigor but have faded and weakened with time and lack of care. Science cannot reverse the effects of time, but can make care in aging more equitable and effective.

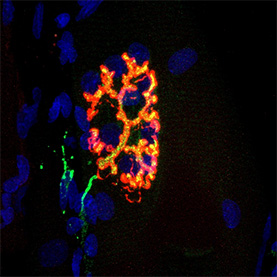

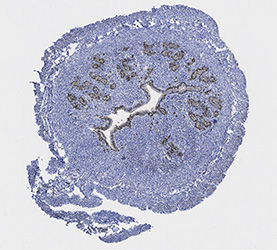

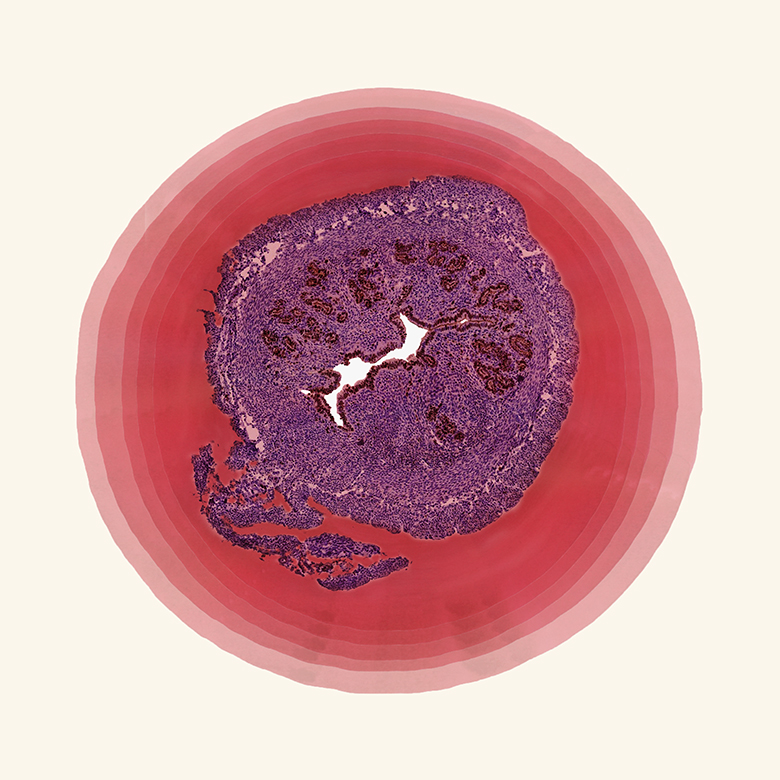

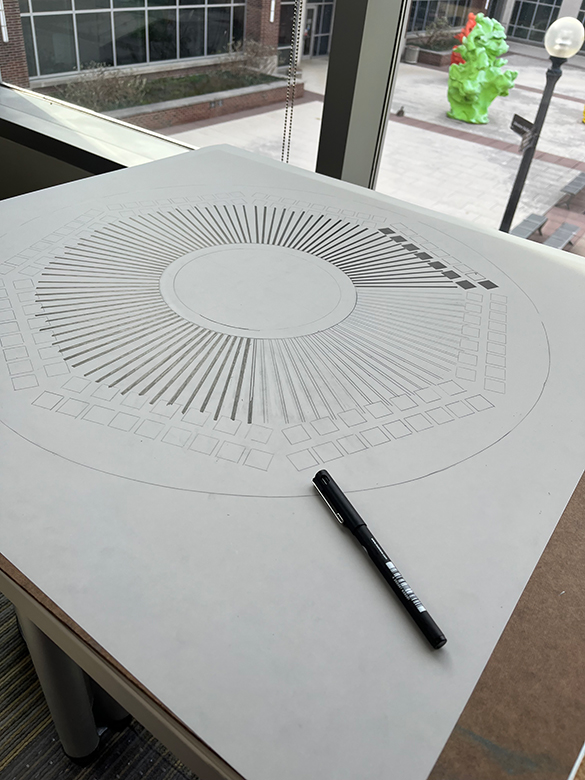

The fertilized egg begins its existence in a state of transience, migrating from the fallopian tube to the uterus. Its survival depends on preparations that predate conception: the inner lining of the uterus thickens, the cells multiplying in preparation for a zygote that may never arrive. If it does, the uterine lining will provide it with a place to anchor and the nutrients it needs to grow. If it does not, the lining will be shed and the reproductive cycle will resume. A symphony of hormonal signaling leads the uterine lining’s cellular dance of proliferation and loss. The artist used pen and ink to draw the viewer into these hidden spaces, defined by what is absent as much as what is present, empty but loaded with potential.

The researchers who contributed to these images are particularly interested in the effect of phthalates, chemicals commonly used to make plastics softer and more flexible. These chemicals can mimic sex hormones and have been linked to challenges in reproductive health. Cross-section imaging of the uterus, combined with stains that identify proliferating cells, can reveal how internal and external factors may disrupt the cellular dance of the estrous cycle.

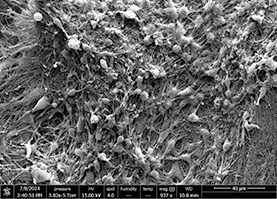

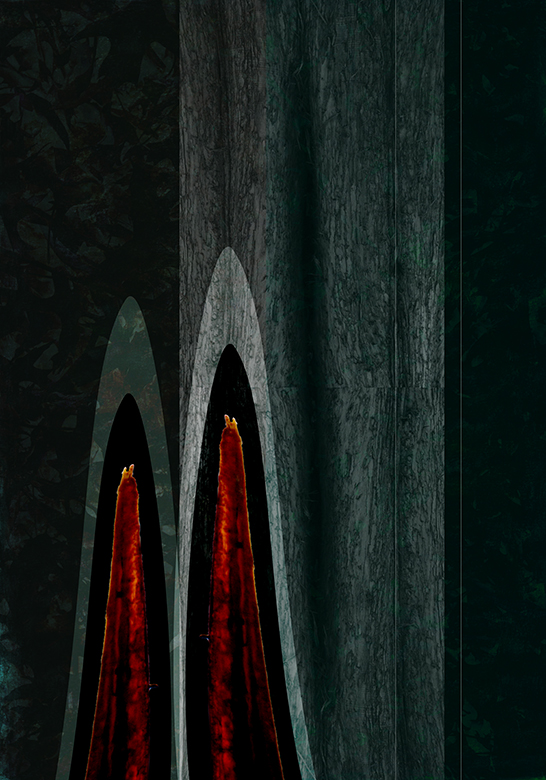

For many people, the sight of a wasp evokes an instinctive fear response. Yet wasps and related insects, although best known for their sting, can also be allies, aiding in pollination and population control of pest insects. This dual identity can be seen in the evolutionary history of one wasp appendage: the ovipositor. Insects lay their eggs through this tube-like structure. In wasps, bees, and some ants, the ovipositor has been co-opted to serve as a stinger. In parasitic wasps like those seen here, the ability of the ovipositor to pierce the protective armor of other insects is simultaneously aggressive and nurturing, enabling the mother to secure a haven for her young by invading the body of their host.

Researchers are exploring the parasitic ovipositor’s puncturing capacity, using 3D microscopy to reverse engineer its assembly of sliding, ratcheting parts. In the pieces seen here, the artist has projected these microscopic structures into a pair of silhouettes. Who do these sleek contours threaten, and who do they protect?

.jpg)

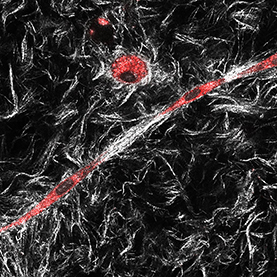

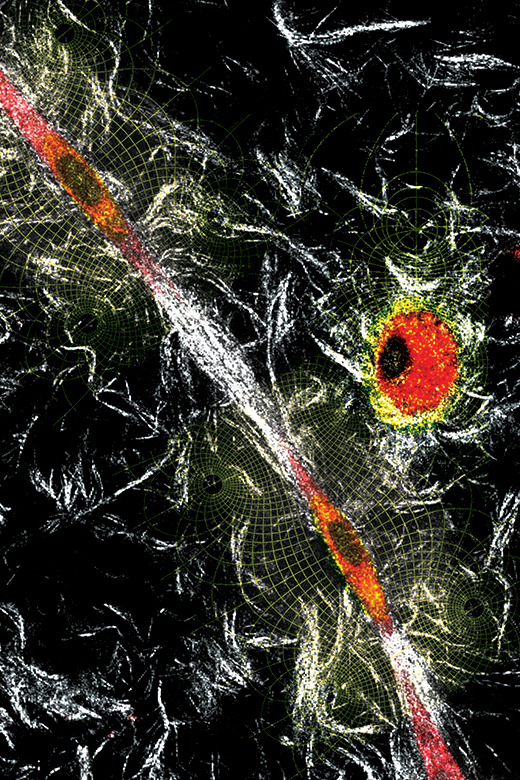

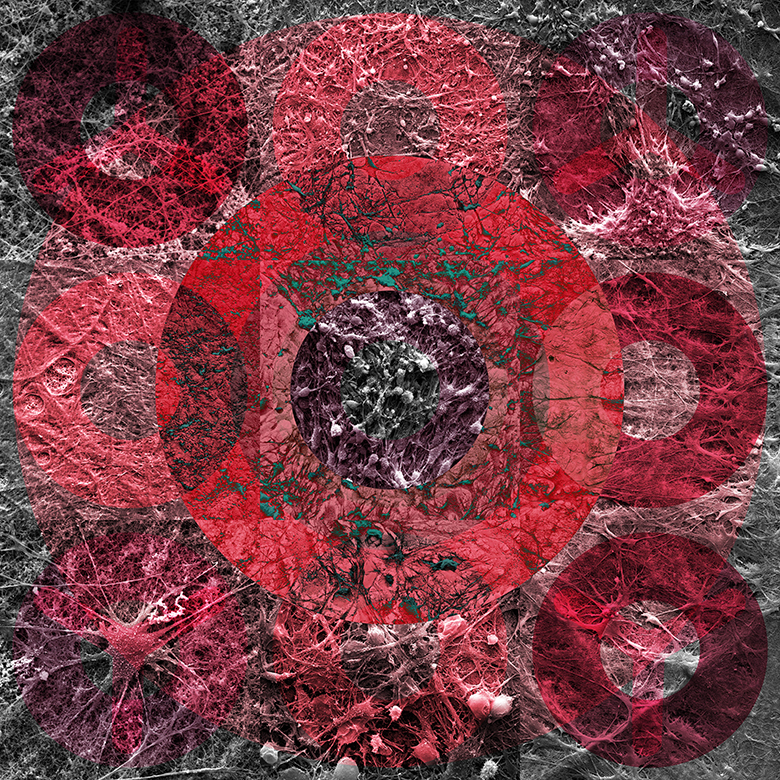

Take a moment to contemplate the forces at play in your life; the constant pushes and pulls from every direction that set off cascades of events, each a potential instantiation of the butterfly effect. On a much smaller scale, our cells are also continually experiencing these pushes and pulls as they interact with other cells and their surrounding environment. The human body is a complex biological machine, and through measurement and visualization, scientists can begin to understand how these small biomechanical forces contribute to overall function, and how mechanical events play a role in the development and progression of diseases like cancer.

The images depict the mechanical interactions of colorectal cancer-associated fibroblast cells (CAFs) as they mechanically change the tumor microenvironment, thereby facilitating cancer cell migration. With the layering of force diagrams and meshes, the artist highlights the tension the red stained CAFs apply to nearby cells. While the collagen fibers between the cells are stretched to form a thick white band, the surrounding fibers buckle from this tensile force. Going forward, these fundamental studies exploring the forces at play in the tumor microenvironment are the first push in a cascade of further research, with the goal to eventually develop improved cancer therapeutics.

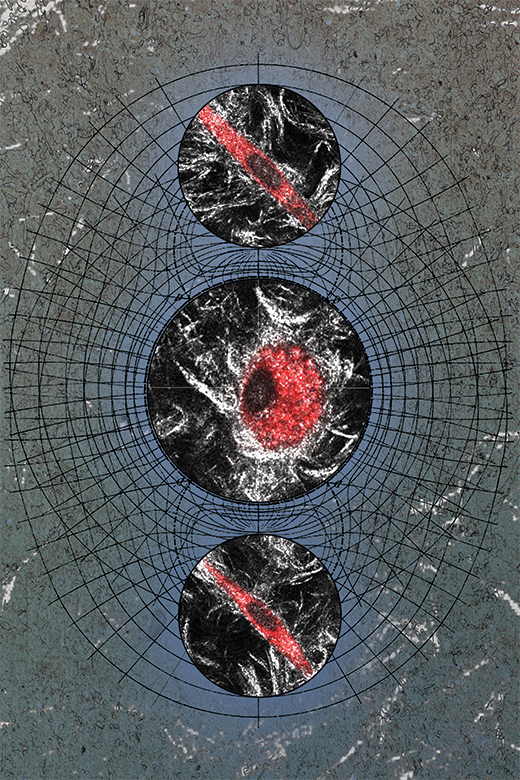

Take a moment to contemplate the forces at play in your life; the constant pushes and pulls from every direction that set off cascades of events, each a potential instantiation of the butterfly effect. On a much smaller scale, our cells are also continually experiencing these pushes and pulls as they interact with other cells and their surrounding environment. The human body is a complex biological machine, and through measurement and visualization, scientists can begin to understand how these small biomechanical forces contribute to overall function, and how mechanical events play a role in the development and progression of diseases like cancer.

The images depict the mechanical interactions of colorectal cancer-associated fibroblast cells (CAFs) as they mechanically change the tumor microenvironment, thereby facilitating cancer cell migration. With the layering of force diagrams and meshes, the artist highlights the tension the red stained CAFs apply to nearby cells. While the collagen fibers between the cells are stretched to form a thick white band, the surrounding fibers buckle from this tensile force. Going forward, these fundamental studies exploring the forces at play in the tumor microenvironment are the first push in a cascade of further research, with the goal to eventually develop improved cancer therapeutics.

When engineers built the first supercomputer in 1960, it filled an entire room and consumed as much power as a neighborhood. Modern supercomputers, which occupy whole buildings and use more power than a small city, can’t yet outpace the computing power and memory capacity of the human brain, which takes up about 80 cubic inches and runs on a 500 calorie meal. Neurons are the cells that perform computations in the brain; some researchers hope to harness their potential through the construction of human-designed living systems.

To do so, it must be possible to encourage neurons to grow and connect with each other outside the body in specified ways. Researchers in the Mind in Vitro project have coaxed neurons to form living networks on ringed and branching shapes cut from filter paper; in these images, the artist has echoed the interwoven texture of the neuronal connections with the texture of the paper itself. A carefully constructed array of microscopic electrodes, its methodical grid reproduced here onto drafting vellum, allows the scientists to speak to the neurons in their language of electrical impulses.

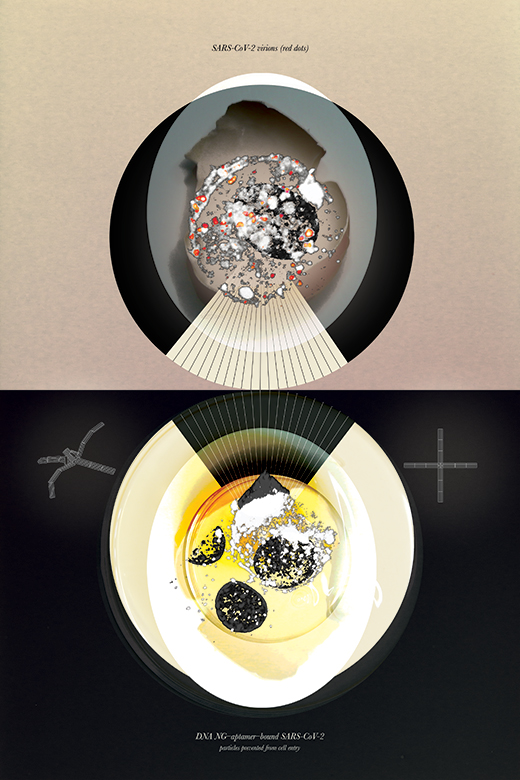

Whether at the arcade, carnival, or mall, the notorious claw machine inevitably drops the prize. As the plushie slips through the mechanical claw for the tenth time, one could only wish that the game was rigged in the player’s favor. When it comes to battling pathogens, how can we grasp what we need to? Inspired by the human hand and bird claws, researchers developed NanoGripper, a microscopic nanorobot specifically rigged to capture and hold SARS-CoV-2 viral particles. Strong and flexible, DNA was repurposed as a structural scaffold and folded back and forth to create the four-fingered nanorobot.

Inspired by the style of Hilma af Klint, the artist has accentuated the polarity of the data, mapping the contrasting scientific images in opposition to each other. When the red viral particles roam free, the cell membrane is vulnerable to the virus, with its penetrability represented by a superimposed image of a broken egg shell. In contrast, when restrained and shielded in the claws of the NanoGrippers, the red virions disappear as SARS-CoV-2 is rendered inactive and unable to enter the cell to cause infection—the egg shell left intact. In the arms race against viruses, perhaps we can rig the game after all through the development of these precision molecular machines.

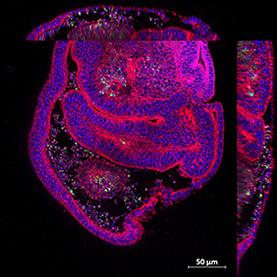

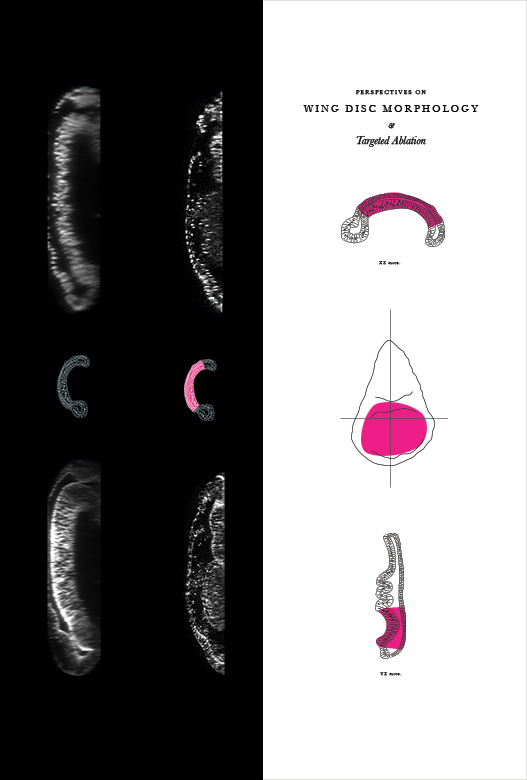

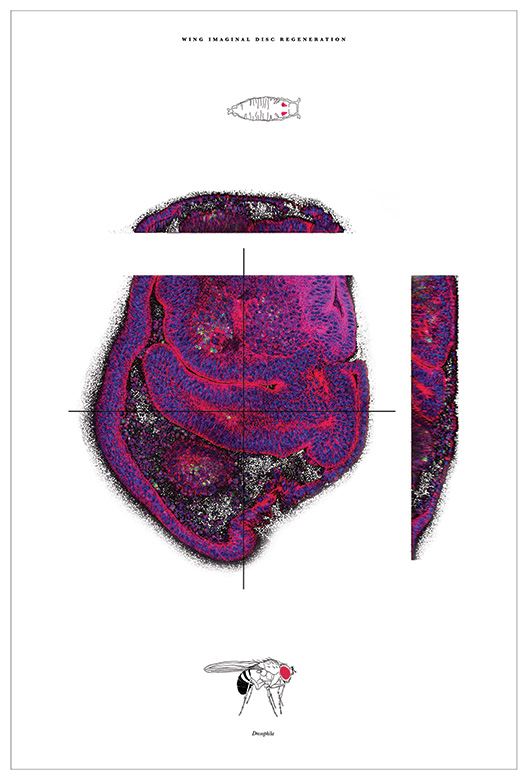

Metamorphosis has the appearance of a magic trick by an unassuming performer: an insect larva briefly withdraws into seclusion and reappears completely transformed. The hidden catalysts of this dramatic turn are imaginal discs, clusters of cells that wait in stasis within the growing larva. When the insect pupates, these cells begin to multiply and diversify, forming antennae, wings, and the long legs of an adult. Researchers study how these cells are able to accomplish this growth to better understand development and discover how to support related processes, including regrowth after injury.

In the study that produced these images, researchers triggered a genetic process that killed cells within the wing imaginal discs of fruit flies. By imaging cross-sections of the recovering imaginal disc, they tracked how the remaining cells—highlighted by their blue centers and magenta outlines—cleared away the debris and repaired the injury. In the final piece, the artist has wrought targeted destruction to reveal hidden processes; a carefully structured order lies beneath seeming disorder.

Metamorphosis has the appearance of a magic trick by an unassuming performer: an insect larva briefly withdraws into seclusion and reappears completely transformed. The hidden catalysts of this dramatic turn are imaginal discs, clusters of cells that wait in stasis within the growing larva. When the insect pupates, these cells begin to multiply and diversify, forming antennae, wings, and the long legs of an adult. Researchers study how these cells are able to accomplish this growth to better understand development and discover how to support related processes, including regrowth after injury.

In the study that produced these images, researchers triggered a genetic process that killed cells within the wing imaginal discs of fruit flies. By imaging cross-sections of the recovering imaginal disc, they tracked how the remaining cells—highlighted by their blue centers and magenta outlines—cleared away the debris and repaired the injury. In the final piece, the artist has wrought targeted destruction to reveal hidden processes; a carefully structured order lies beneath seeming disorder.

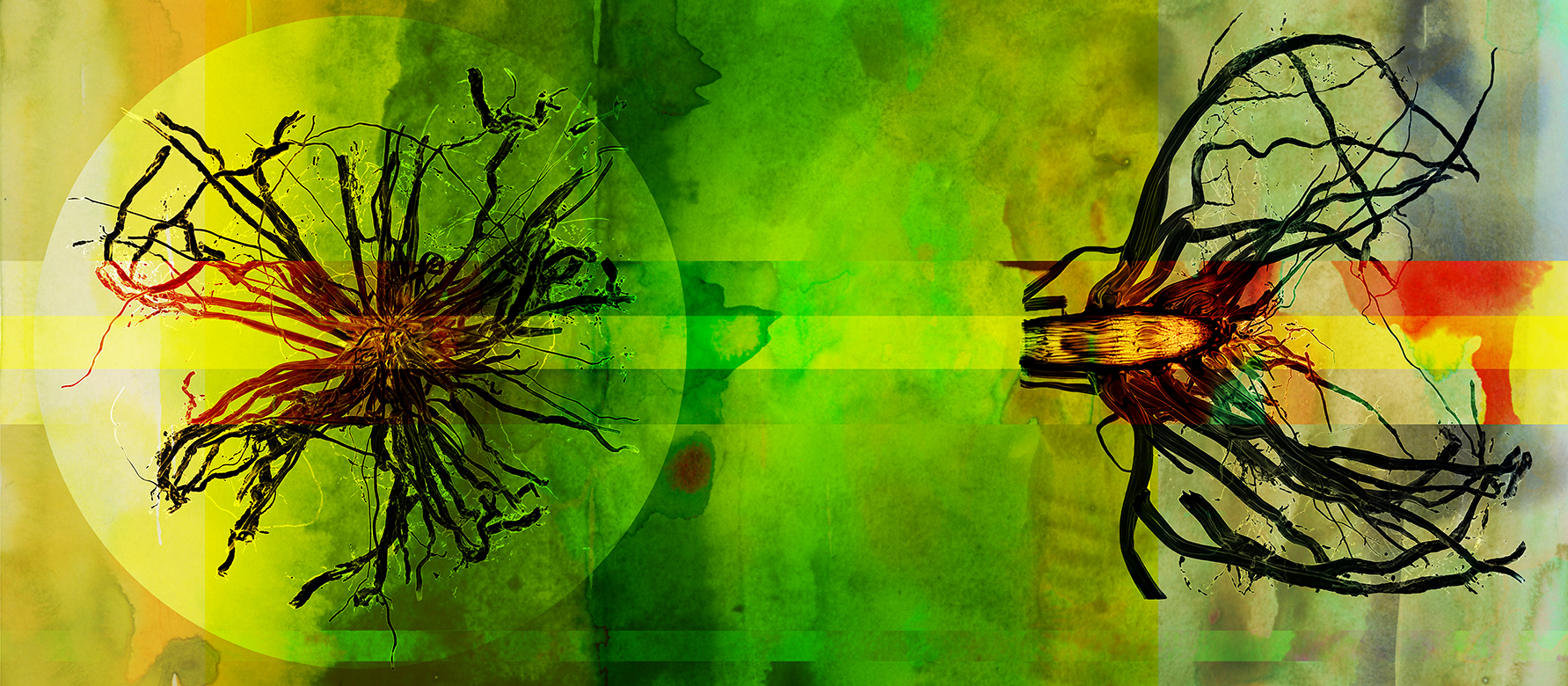

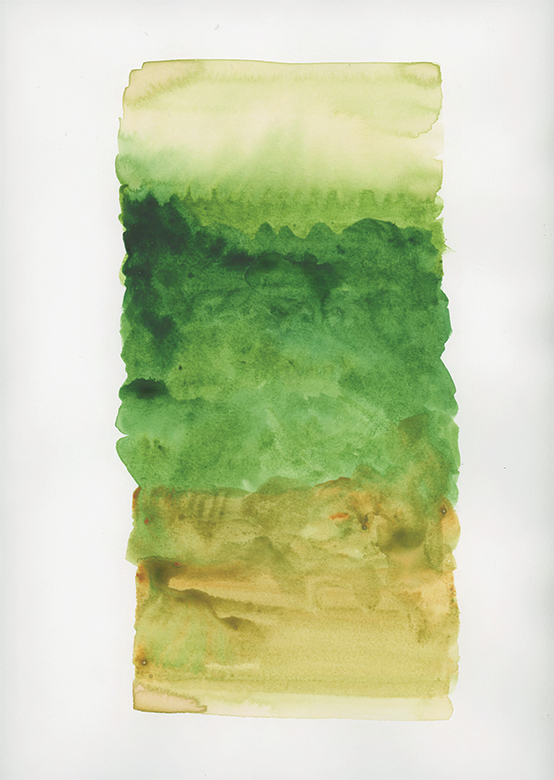

With a quick trip to the grocery store, people can access a wide variety of food crops from across the globe—fruits, vegetables, grains, and spices—with just the swipe of a card. Even juxtaposed with the vast expanses of corn and soybeans growing in the fertile Midwest soils surrounding Champaign-Urbana, it can be easy to take for granted the steady availability of food staples. But with our ever-changing planet and growing human population, are these farming and food cultures sustainable? By studying the physical properties of sorghum roots, scientists can begin to design plants better suited for surviving drought and limited nutrient conditions.

Using layers of watercolor paint, the artist draws attention to the conditions that lead to different growth outcomes. The rich vibrant colors represent plants with sufficient water intake in contrast to the bleak colors of drought in the second image. As you observe the images in the pieces, what differences do you notice? Are there changes in the size, shapes, angles, and thickness of the roots? By coupling physical observation with genomic data, we look towards building a resilient, food secure future where both plants and humans can thrive.

With a quick trip to the grocery store, people can access a wide variety of food crops from across the globe—fruits, vegetables, grains, and spices—with just the swipe of a card. Even juxtaposed with the vast expanses of corn and soybeans growing in the fertile Midwest soils surrounding Champaign-Urbana, it can be easy to take for granted the steady availability of food staples. But with our ever-changing planet and growing human population, are these farming and food cultures sustainable? By studying the physical properties of sorghum roots, scientists can begin to design plants better suited for surviving drought and limited nutrient conditions.

Using layers of watercolor paint, the artist draws attention to the conditions that lead to different growth outcomes. The rich vibrant colors represent plants with sufficient water intake in contrast to the bleak colors of drought in the second image. As you observe the images in the pieces, what differences do you notice? Are there changes in the size, shapes, angles, and thickness of the roots? By coupling physical observation with genomic data, we look towards building a resilient, food secure future where both plants and humans can thrive.

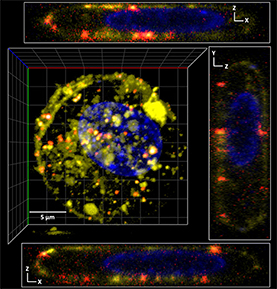

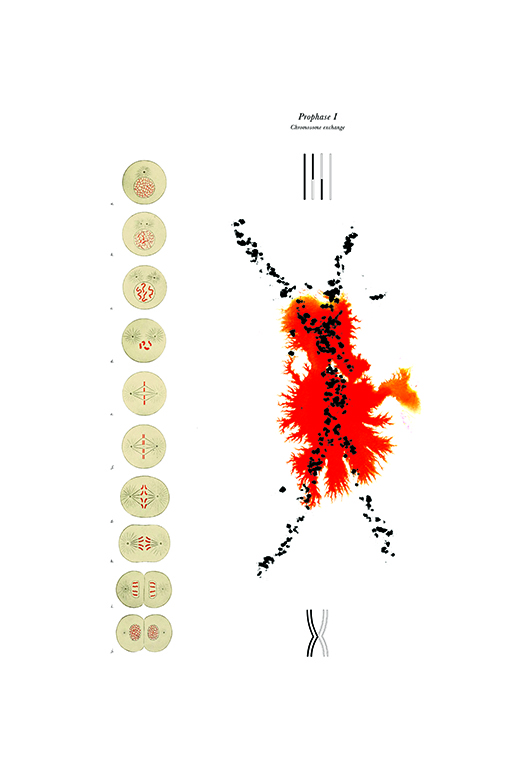

Egg cells are formed by the process of meiosis, in which pairs of chromosomes first line up, then pull apart, dancing a microscopic Virginia Reel. This dance of generations actually begins in the female fetus months before birth; the reel is suspended, the immature eggs left in an arrested state of meiosis for years until puberty. If a step of the dance has gone amiss, the eventual reproductive health outcome often appears disconnected from its original cause.

Through these pieces, the artist highlights meiosis, its many stages, and the evolution of the technologies that let us observe it. The imagery captures prophase I of meiosis in super resolution, zoomed in 100,000 times smaller than a human hair. As the cell prepares for meiotic dormancy, threads of DNA are organized and stabilized in a process choreographed by proteins seen here in fluorescent shades . As scientists visualize meiotic processes, they gain insights into infertility, miscarriages, and genetic disorders in pursuit of improving reproductive health and public health outcomes.

Egg cells are formed by the process of meiosis, in which pairs of chromosomes first line up, then pull apart, dancing a microscopic Virginia Reel. This dance of generations actually begins in the female fetus months before birth; the reel is suspended, the immature eggs left in an arrested state of meiosis for years until puberty. If a step of the dance has gone amiss, the eventual reproductive health outcome often appears disconnected from its original cause.

Through these pieces, the artist highlights meiosis, its many stages, and the evolution of the technologies that let us observe it. The imagery captures prophase I of meiosis in super resolution, zoomed in 100,000 times smaller than a human hair. As the cell prepares for meiotic dormancy, threads of DNA are organized and stabilized in a process choreographed by proteins seen here in fluorescent shades . As scientists visualize meiotic processes, they gain insights into infertility, miscarriages, and genetic disorders in pursuit of improving reproductive health and public health outcomes.

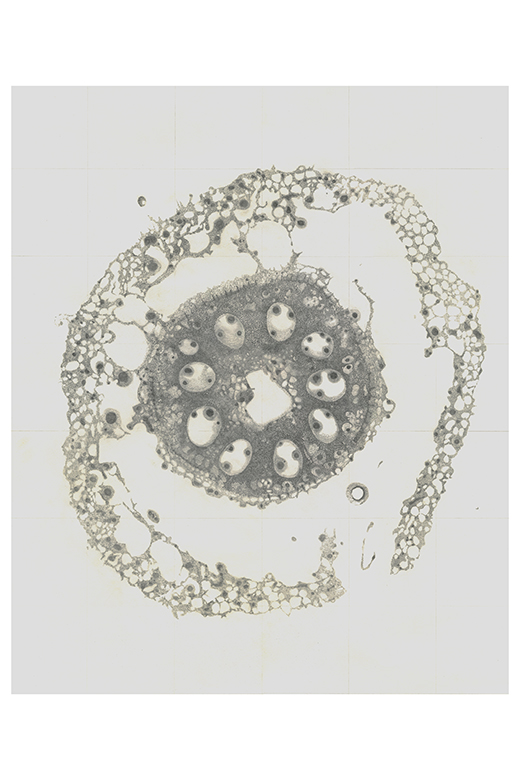

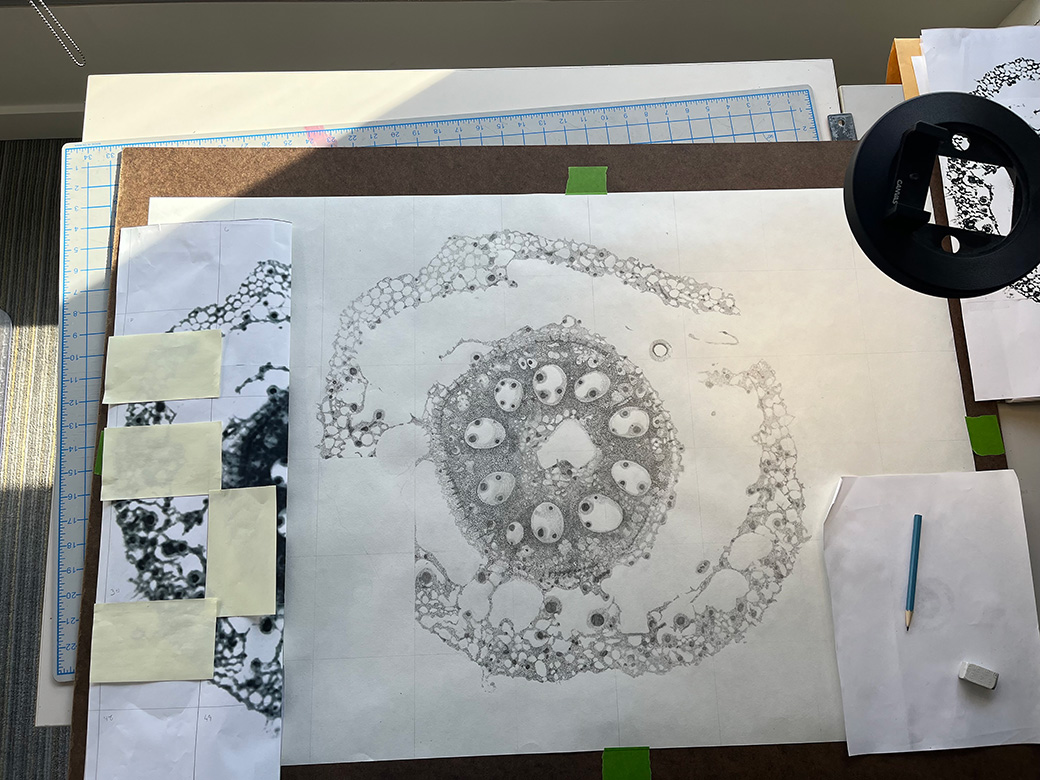

Plants, quiet but omnipresent, play numerous roles in the human experience—providing oxygen to breathe, food for nourishment, and beauty in our environments. As we encounter stresses and challenges in our daily lives, we can also turn to plants to learn about resiliency. Rooted in one place, plants have evolved unique mechanisms to deal with stressors arising from environmental flux. Corn and rice, as well as other semi-aquatic and wetland plants, have stems composed of aerenchyma, spongy air-filled cavities that run up and down, connecting the underground body to the air above and acting as internal highways for gas transport.

In this hand-drawn piece, the artist pays homage to the beauty of resilience. Each precise mark of charcoal comes together to showcase the intricacies in the cross section of the corn root. As you examine the shapes and patterns embedded in the tissue slice, also take notice of the empty space. During drought conditions, the aerenchyma degrades so the plant can save energy and redistribute its power to maintain growth patterns. Fragmented or whole, the corn plant adapts and lives on in a true testament to endurance through flexibility and endurance.

View Gallery

1

/

10